- Accueil

- > Livraisons

- > Sixième livraison

- > Pro anima ipsius testatoris

Pro anima ipsius testatoris

On the Presence of the Goldsmith Francesco da Milano in his own Work

Par Mandy Telle

Publication en ligne le 07 avril 2025

Résumé

In 1377, the goldsmith Francesco from Milan was commissioned by Elisabeth Kotromanić (ca. 1340-87), Queen of Hungary and wife of Louis I. of Anjou (d. 1384), to create a monumental tomb-shrine for the body of St. Simeon. Although the contract between the parties provides specifications for the pictorial program, there are no such contractual stipulations for the donor’s or the artist’s inscription and his self-portrait. However, these features can be seen on the physical shrine. While the client’s motivation for her donation has been examined thoroughly from different perspectives, the function of the goldsmith’s written and pictorial presence has not yet been clarified in detail.2 This article aims to shed light on this issue by analyzing a possible connection to Francesco’s social position (as partly revealed by contemporary written sources), possible scenarios of action in which the shrine was involved, circle of recipients to which these self-references could have been visible, and how they might have been received.

En 1377, l’orfèvre milanais Francesco est chargé par Elisabeth Kotromanić (ca. 1340-87), reine de Hongrie et épouse de Louis Ier d’Anjou (mort en 1384), de réaliser un tombeau-reliquaire monumental pour le corps de saint Siméon. Si le contrat entre les parties fournit des indications pour le programme pictural, on n’y lit aucune précision contractuelle pour l’inscription du donateur ou de l’artiste et pour son autoportrait. Cependant, ces éléments sont visibles sur la châsse. Alors que la motivation de la donatrice a été examinée sous différents angles dans le cadre des recherches sur cet objet, la fonction la présence épigraphique et iconographique de l’orfèvre de l’orfèvre n’a pas encore été élucidée en détail. Cet article vise à éclaircir cette question en analysant un lien possible avec la position sociale de Francesco (telle qu’elle est partiellement révélée par les sources écrites contemporaines), le scénario des actions dans lesquelles la châsse était impliquée, le cercle de destinataires auquel ces autoréférences auraient pu être accessibles et la manière dont elles auraient pu être reçues.

Mots-Clés

Table des matières

Texte intégral

Introduction

1In the Dalmatian coastal town of Zadar, the production of secular and sacred goldsmith’s work flourished in the thirteenth and fourteenth century, as evidenced not only by the quantity and quality of surviving works but also by the establishment of a “goldsmith’s alley” (contrata aurificum), which is mentioned in a document dated 1274. This situation intensified in the second half of the fourteenth century, as more than ten active goldsmiths from Zadar are documented, another 21 from various Croatian cities and six whose names indicate their Italian origin, pointing not only to the migration radius and mobility of this profession, but also to the diverse international links in the field of artistic exchanges.3 Some of the masters left signatures on their works. Amongst them were Toma Martinušić (also known as Toma Martinov or Tommaso di Martino; his work as a goldsmith in Zadar can be documented from 1495 to 15274) and Francesco da Milano (died around 1400), who both worked on the shrine of St. Simeon (fig. 1).5

Fig. 1: Francesco da Milano, Tomb-Shrine of St. Simeon, dated 1380, front, Zadar, Church of St. Simeon.

Photo: Živko Bačić, source: Archdiocese of Zadar.

2While Toma contributed the interior fittings with silver plates that show figures of Zadar saints as a later addition, Francesco was the person originally commissioned with the completion of the tomb-shrine by contract in 1377. The commissioner was the Hungaro-Croatian Queen Elizabeth Kotromanić (ca. 1340-87), daughter of the Bosnian ban Stephen and second wife of King Louis of Hungary (r. 1342-82).6 This is the only shrine that bears both an artist’s signature and for which the text of the contract has survived. Because these circumstances make this shrine particularly fruitful for a case study that examines the signatures of goldsmiths on their works, this paper focuses on the motivation and function of the artist’s inscription and offers a contribution to the research on medieval artists’ signatures.7

3Artists’ signatures in the Middle Ages can be found in architecture, sculpture, painting and goldsmith’s art, and have the potential to be genuine primary sources for the identification of the people involved in the creation of the artifacts, of historical contexts, spatial and temporal, cultural-historical and social categorization of the work and those involved in its creation. In this paper, “signatures” are defined as inscriptions and depictions by one or more artists in his or her work. This interpretation is closely based on André Chastel’s definition, according to which “[t]he signature [...] is any indication of the author of a work given by a signaling process, apart from the means of art themselves.”8

The shrine of St. Simeon: images and inscriptions

4The exterior of the shrine is made of gilt-laminated silver (worked in repoussé) over a core of cypress wood.9 It is 192 centimeters long, 62,5 centimeters wide and with the roof 127 centimeters high. When the city of Zadar had to pay 30,000 gold ducats in taxes to King Sigismund, the original four supporting silver angels were probably melted down in 1390 – just ten years after the shrine was completed. Today, four baroque angels support the shrine that is placed above the main altar of the Church of Saint Simeon. Two of them are made of stone, the other two were modelled by Francesco Cavrioli and cast in 1647 from the bronze of cannons from the Turkish army, which the Venetians had plundered and given to Zadar (fig. 2).10

fig. 2: Francesco da Milano, Tomb-Shrine of St. Simeon, dated 1380, detail: The Presentation in the Temple, Zadar, Church of St. Simeon. Photo: Mladen Grčević.

Photo: Mladen Grčević, source: Marijan Grgić, Der Gold und Silberschatz von Zadar und Nin, Zagreb, Turistkomerc, 1972, p. 103.

5The shrine has the form of a rectangular, box-shaped sarcophagus with a pitched roof; on the front side the life-size reclining prophet Simeon is shown. An embossed inscription in Gothic minuscule around the neck and on the wrist identifies the effigy as sanctus Simeon Propheta. Below the roof, the rectangular front of the tomb-shrine is divided into three pictorial panels. The central field depicts the Presentation of the infant Jesus in the Temple (fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Giotto di Bondone (c. 1266–1337), “The Presentation in the Temple”, c. 1303/10, fresco, Padua, Cappella degli Scrovegni.

source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Giotto_di_Bondone_-_No._19_Scenes_from_the_Life_of_Christ_-_3._Presentation_of_Christ_at_the_Temple_-_WGA09197.jpg (12.02.2024).

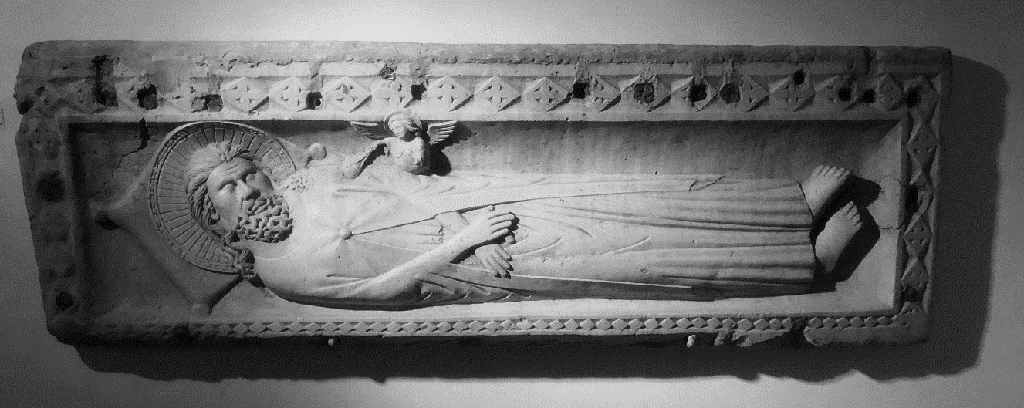

6Simeon the prophet is shown holding the infant in the presence of Mary, Joseph, two doves and the prophetess Anna (Luke 2:21-40).11 This scene seems to allude to Giotto’s fresco in the Arena Chapel in Padua (1304-1306), (fig. 4) but as Francesco leaves out two figures and the child turns towards Mary, his pictorial solution could quote a painting now in the Gardner Museum in Boston, also attributed to Giotto (fig. 5).12

Fig. 4: Attributed to Giotto di Bondone (c. 1266–1337), “The Presentation in the Temple”, c. 1320, Tempera on panel, Boston, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Accession number P30W9.

Source: https://www.gardnermuseum.org/experience/collection/12894 (05.02.2024).

Fig. 5: Francesco da Milano, Tomb-Shrine of St. Simeon, dated 1380, detail: The Theft of a finger, Zadar, Church of St. Simeon.

Photo: Mladen Grčević, source: Marijan Grgić, Der Gold und Silberschatz von Zadar und Nin, Zagreb, Turistkomerc, 1972, p. 112.

7Almost all the surfaces of the shrine that do not show figures of persons are decorated with tendrils and meandering rosettes of finely chiseled foliage. On the left-hand panel, the legend about the discovery of the relic is depicted. According to this legend, the body of St. Simeon came from Constantinople to Zadar in 1203 on a ship on its way to Venice and sought shelter in the city from a storm.13 On that very ship, a nobleman who stayed at the hospice of a monastery in the periphery of Zadar claimed that the body was that of his brother who had died during their journey. He was allowed to bury the body in the monastery cemetery. When the nobleman fell ill and died, the monks found a note that revealed that the body was that of St. Simeon, and they decided to unearth the body during the night for its veneration in their monastery. The image shows the monks on the right side of the panel. On the left side, the panel shows three town rectors, all of them were visited by St. Simeon in a dream, where he revealed that he was buried in the monastery cemetery. The rectors went to the site and surprised the monks while they were digging up the grave and passed on the news to the archbishop, who insisted that the relics were to be translated to the church of the Assumption for veneration.14

8On the right, the third composition possibly depicts a ceremonial reception of King Louis of Anjou in the city harbor. It possibly refers to the confirmation of the privileges of the citizens from Zadar as a consequence of a peace treaty signed on February 18th, 1358, that resulted in Louis ending hostile attacks against Venice in exchange for Dalmatian territories.15 The two triangular narrow sides of the shrine show King Louis’ helmet with the coat of arms of Hungary and the House of Anjou and the letters L(udovicus) and R(ex). The left-hand rectangular panel of the narrow side shows the calming of a sea storm by St. Simeon.16 The corresponding opposite rectangular panel depicts the theft and return of the saint’s finger by a woman sometimes identified as Elizabeth, though she does not wear a crown (fig. 6).17

Fig. 6: Francesco da Milano, Tomb-Shrine of St. Simeon, dated 1380, backside, Zadar, Church of St. Simeon.

Photo: Živko Bačić, source: Archdiocese of Zadar.

Fig. 7: Francesco da Milano, Tomb-Shrine of St. Simeon, dated 1380, backside, detail: The donation of the shrine, Zadar, Church of St. Simeon.

Photo: Mladen Grčević, source: Marijan Grgić, Der Gold und Silberschatz von Zadar und Nin, Zagreb, Turistkomerc, 1972, p. 107.

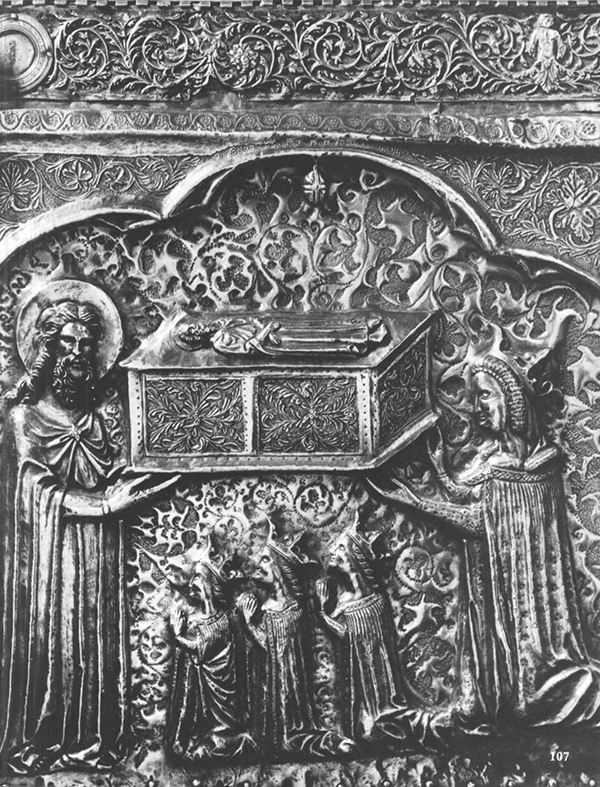

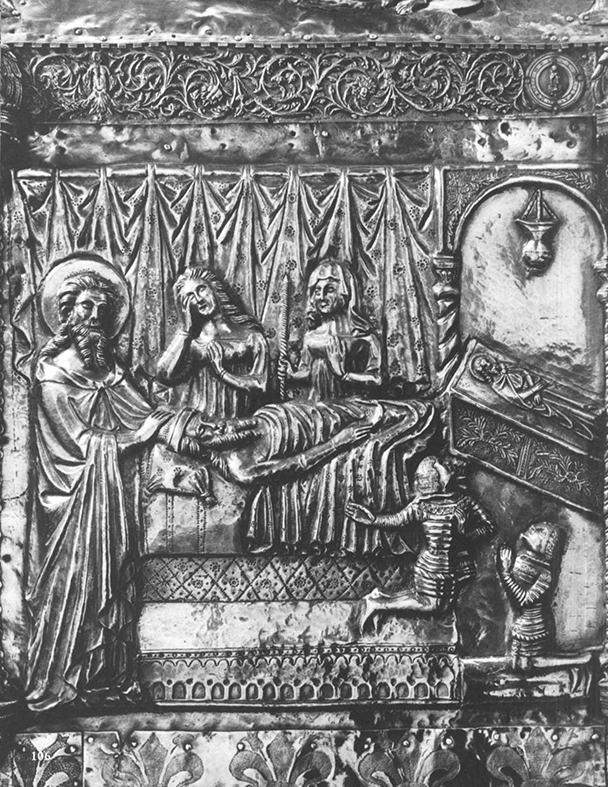

9Similar to the front of the shrine, the long rectangular side of the back is also divided into three pictorial areas (fig. 7). On the left, the queen presents the shrine to St. Simeon in the presence of her three daughters (fig. 8). On the right-hand side is depicted the death of her father, ban Stjepan II. Kotromanić of Bosnia, in presence of St. Simeon (fig. 9). These two scenes frame the central inscription (fig. 10 a, b), written in high relief on an almost rectangular panel, surrounded on all four sides by foliage, with the coat of arms of Louis of Anjou in the corners. The inscription is written in Gothic majuscules and refers to the donor and patron, Queen Elisabeth, and her votive offering to St. Simeon, emphasizing the fact that the saint held Christ in his arms. The text is spread over ten lines pressed into the inscription panel; the eleventh line ends shortly before the center of the lines above; the remaining space appears blank. The inscription reads:

SYMEON:HIC·IVSTVS·Y

EXVM·DE·VIRGINE·NAT

VM·VLNIS:QVI·TENVIT

HAC·ARCHA:PACE:QVIE

SCIT·HVNGARIE·REGI

NA·POTENS:ILLVSTRI

S:ED·ALTA:ELIZABET·I

VNIOR:QVAM·VOTO:CON

TVLIT·ALMO ANNO·MI

LLENO:TRECENO:OCTV

AGENO·18

Fig. 8: Francesco da Milano, Tomb-Shrine of St. Simeon, dated 1380, backside, detail: The Death of ban Stjepan II. Kotromanić of Bosnia, Zadar, Church of St. Simeon.

Photo: Mladen Grčević, source: Marijan Grgić, Der Gold und Silberschatz von Zadar und Nin, Zagreb, Turistkomerc, 1972, p. 106.

10Separate from this inscription, under a fine horizontal line, with smaller stylized letters in Gothic minuscule, and gathered in a single line is the engraved artist’s signature that reads:

+ HOC·OPVS·FECIT·FRANCISCVS·D·MEDIOLANO·.

11Connecting the inscription in logical rows, it reads:

Symeon hic iustus Jesum de Virgine natum

Ulnis qui tenuit, hac archa pace quiescit,

Hungarie regina, potens, illustris et alta,

Elyzabet iunior quam voto contulit almo.

Anno milleno, treceno, octuageno.

Hoc opus fecit Franciscus de Mediolano.19

Fig. 9: Francesco da Milano, Tomb-Shrine of St. Simeon, dated 1380, backside, detail: The inscription panel, Zadar, Church of St. Simeon.

Photo: Živko Bačić, source: Archdiocese of Zadar.

Fig. 10: Francesco da Milano, Tomb-Shrine of St. Simeon, dated 1380, backside, detail: The inscription panel, the artist’s inscription exceeds the panel frame, Zadar, Church of St. Simeon.

Photo: Mandy Telle.

12The inscription has a verse form with hexameters and some irregularities, such as the epithet iunior and the name Symeon. The formula hoc opus fecit and the indication of the local origin of the goldsmith (or his family’s) Mediolano are not following the metric inscription.20 Hence, the part with the goldsmith’s signature is a prose part, which is quite common in medieval Latin inscriptions. The translation of the inscription reads:

“Here, in this chest, donated by the mighty, exalted and sublime Elizabeth the Younger, Queen of Hungary in the year one thousand three hundred and eighty, in fulfilment of her vow, rests peacefully Simeon the Righteous, who held Jesus, born of the Virgin, in his arms. This work was made by Francis of Milan.”21

13While the dedicatory inscription is ostentatiously designed for amplified visibility, the artist’s inscription is subordinated in a crowded line that exceeds the frame of the inscription panel on the right. These epigraphic, paleographic and prosodic differences between the two inscriptions signal by their size a hierarchical difference between the royal donor and the secular goldsmith. Furthermore, these differences raise the question of whether the inscriptions, and especially the signature of the artist, belong to the original conception of the shrine. The object underwent modifications over time. In the seventeenth century, the goldsmiths Benedetto Libani from Zadar and Constantino Piazzalonga from Venice repaired and shortened the casket by about ten centimeters in length and three centimeters in width and possibly added twisted columns with angel heads, that separate the individual compositions from each other, if the latter ones were not already added by Toma Martinušić.22 It is unknown whether Francesco had already made similar columns. Their later addition can be technically verified, as one of them overlays a coat of arms. It is plausible that, in the original design, the coat of arms which serves as a display of the ruling dynasty of the Anjou and a reminder that a member of that dynasty donated the shrine, was meant to be seen and hence, originally not hidden underneath decorative features. Those modifications further imply a slightly different original form of the tomb-shrine.

14Were parts of the inscription also moved in the process? It seems more plausible that the inscription panel was considered in the genesis of the work and hence, that it belongs to the original planning of the work. It is to be assumed that the inscription was either an oral agreement or agreed upon in another written form. Furthermore, it remains uncertain whether Francesco himself executed both inscriptions or only his signature; or if another person or several craftsmen executed both inscriptions. The learned form in metrical style suggests that at least the donor’s inscription was designed by a literate person, while the artist’s signature follows a common formular in the style of the “N. me fecit” inscriptions found throughout artworks since Antiquity and throughout of the medieval period.23

15On the top of the roof, on the rear side, two depictions of miracles that took place in the presence of the saint’s body frame the image of the goldsmith Francesco da Milano working on the shrine, more precisely on one of the small supporting columns (fig. 11).24 A discourse on the artist’s pride and humility can open up here: Could he leave his likeness to the present and future recipients due to his social status as an artist working for royalty or due to his profession and skill as a goldsmith? In the same time, he humbly kneels in front of his own work, depicting the strenuous labor he puts into effect.25 Here the goldsmith looks back at the unknown young man and woman who have come to venerate the saint, as if he wanted to say: Behold, this is the shrine of the saint, and it is me who created it with my own hands, labor and God-given talent. That means, that the signature should not only appeal to heavenly, but also to earthly eyes. The goldsmith is a creator himself, but here, he functions as a mediator between the viewers and the shrine, between the recipient and the true creator, God, through whose will he created the shrine. Jacqueline Leclercq-Marx described the effect of the signature in similar cases as such: “Car ce n'est pas uniquement à Dieu que l'humble signature s'addresse, même quand elle s'accompagne, tel un ex-voto, d'une formule pie. Elle est également une tentative d'établir avec celui qui la regarde inscrite dans l'oeuvre un dialogue à la fois soudain et sans âge, dans la mesure où la signature est un discours a retardement, et même un discours d'outre-tombe.”26

Fig. 11: Francesco da Milano, Tomb-Shrine of St. Simeon, dated 1380, backside, detail: Self-portrait of the goldsmith, Zadar, Church of St. Simeon.

Photo: Živko Bačić, source: Archdiocese of Zadar.

16The rectangular front of the shrine, on hinges, can be unlocked and dropped down, revealing three reliefs on the obverse side of this panel (fig. 12): Here, from left to right, are depicted three miracles associated with the power of the relic. Once open, the body of the saint is visible.27

Fig. 12: Tomb-Shrine of St. Simeon, dated 1380, front panel dropped down, depictions of miracles, Zadar, Church of St. Simeon.

Photo: Živko Bačić, source: Archdiocese of Zadar.

17The interior of the shrine is decorated on the rear rectangular side (that is the side behind the body of the saint and opposite the opening) with silver plaques, showing yet another Presentation in the Temple; saints Chrysogonus, Anastasia and Zoilus, who were patrons of the city of Zadar, under columnated arcades with pseudo-Corinthian capitals. The bases show tabulae ansatae, amongst them one with a bulging edge. It contains a dedicatory inscription that consists of ten lines that read:

DIVO SIMEONI IVUSTO PROPHETAE

DICATVM

IOANNE • ROBOBELLO • ANTISTITE

IOANNE • BOLANO • PRAETORE •

FRANCISCO • MARCELLO • VRBIS

PRAEFECTO

ZOILO • DENASIS • ET• MACRO •

CHRI

SOGONO• ARCAE• PROCVRATORIBVS •

MCCCCXCVII DIE VLTIMO MENSIS APRILIS28

18Underneath is an engraved scroll with a two-line inscription, slightly rolled inwards at the corners (fig. 13):

OPVS • TOMAS • MARTINI • DE • IADRA

• ROGO • VOS • FRATRES • ORATE • PRO • ME29

19The translation of the artist’s inscription reads: “[This is] the work of Tomas Martini of Zadar. I ask you brothers to pray for me”. The previous, longer dedicatory inscription names the archbishop, the city rector and the city captain as well as two church administrators. The most important information is provided by the date on this plaque: April 30, 1497. Toma is known from several documents from the beginning of the 16th century and he died around 1531.

Fig. 13: Tommaso di Martino, Reliquary Shrine of Saint Simeon, dedicatory inscription (detail of lining inside the shrine), 1497, Zadar, Church of Saint Simeon.

Photo: Živko Bačić, source: Archdiocese of Zadar; STANKO KOKOLE, op. cit., p. 113, fig. 4.

20This is the only work by the goldsmith Toma Martinov with a signature and a date.30 The signature implies the goldsmith’s hope for prayer requests in his name with regard to the provision for the afterlife.

21The pictorial program of the shrine can therefore be categorized into a number of different themes: the arrival and translation of the body of Saint Simeon; miracles he performed and punishments of unbelievers; the role of the relics in oath taking and oath breaking; historical narratives of Elisabeth’s royal family, which are intended to demonstrate both their religious attitudes, piety, status and political achievements and, finally, the epigraphic presence of two goldsmiths and the pictorial presence of Francesco da Milano.

22The description of the shrine sheds lights not only on the compositional aspects of its making, but also on the appreciation of the precious tomb-shrine throughout time and certain challenges. Certain features of the shrine were added throughout time, altered and also left out. While the original shrine dates back to Francesco da Milano, several artists worked on it throughout the centuries, such as Toma Martinov and later on, Francesco Cecchelli who created the bronze angels that seemingly carry the shrine. Both Francesco da Milano and Toma Martinov left their names on their work. As this study focusses on Francesco da Milano, the following part will analyze if the still existing contract between him and his royal commissioner holds information as to why the goldsmith was allowed to be represented by name and image on his work.

The contract

23The contract31 for the shrine is kept in the State Historical Archives in Zadar.32 It suffered water damages during its transport between Venice and Zadar in the turmoil of the Second World War. In the following, the legible or easily reconstructable parts of the contract are shown in italics; the segments in parenthesis suggest hard or non-legible parts which are the most plausible additions, while square brackets signify additions by Monika Gussone.33 The contract for the construction of the shrine was drawn up in Zadar in the large columned hall of the town council on July 5, 1377.34 The following parties were involved: the client was the master goldsmith Francesco da Mediolano, “son of the late Antonio da Milano, now residing in Zadar”.35 It is stated that Francesco was a habitatore in Zadar, which means a resident, but not a cives, a citizen. The donor, Queen Elisabeth, is also mentioned with all her titles. She was represented by five noblemen from Zadar.36 The notary was the judge and examiner Ser Madius de Fanfogna.37 The contract was concluded in the presence of witnesses, all citizens of Zadar, as well as other unspecified witnesses.38 According to the contract, the queen sent 1000 marks of silver to the city to initiate the making of a precious silver-gilt shrine.39 The shrine was to be completed within one year.40 Francesco exceeded this deadline and needed three years, as the inscription on the shrine states the year 1380. One year is a short period of time for the creation of a monumental goldsmith work. The reasons for the delay are unknown, but could lie in the provision of materials, in the organization of the workshop or difficulties in technical implementation. It is clear from the contract that Francesco was not provided with the entire amount of gold and silver at once, but 50 marks each of silver, gold and mercury. The wages were paid in stages, depending on the progress of the work.41 This arrangement surely was also intended to prevent misappropriation of materials by the goldsmith. Francesco received a one-off payment of 200 ducats relatively soon after the contract was signed.42

24There are contractual specifications for both the material to be used and the pictorial program: “and of that alloy and quality of silver to that form and replica of the said silver shrine to be made, and with those forms, images, signs, wonders and representations of our Lord Jesus Christ as presented on the altar, as this shrine shall be given and made on cotton paper, in likeness with the said silver shrine to be made; these figures must all be raised, as shall be proper, and the said shrine shall be gilded within and without, and from above and below, altogether with all those figures which shall be gilded.”43 The depiction in the Temple was most likely drawn on the aforementioned cotton paper (carta bumbicina). It is not clear from the contract whether Francesco da Milano made this preparatory drawing himself or whether he worked from another artist’s model. Francesco had to work ad similitudinem from this preparatory drawing, which means as similar as possible to the given drawing. This indicates that the drawing was approved by the client and reflected her specific wishes for the work to be created. All figures were to be executed in relief and the shrine was to be completely gilded, even on the underside. On the one hand, no expense or effort should have been spared to give the saint a worthy shrine, while on the other hand, the desire for a gilded underside may also suggest an intention to present the shrine in an elevated position so that worshippers could either walk or kneel beneath it. By legally binding himself to the contract, the goldsmith takes on high personal risks. In the event of damage, he is liable with his entire property and that of his family in future generations and during future reigns.44

25The contract not only gives instructions on the working conditions for the goldsmith and legal implementations but it also sheds light on the motives of the Queen for commissioning the shrine that is not only the most important monumental goldsmith work of Croatia, but still venerated to this day in Zadar. In the time of the making, the people of Zadar already venerated the city patron Saints Anastasia and Chrysogonus. The following paragraph will therefore discuss – based on the contract, the shrine’s inscription and pictorial program, but also socio-political and religious aspects beyond these sources – possible motives for which the Queen had to focus especially on Saint Simeon and to commission a precious tomb-shrine for his earthly remains.

The Queen and the Saint: Motives for Commissioning the Shrine

26It is necessary to analyze why exactly it was crucial for the Queen to focus on the body of St. Simeon. Who was this saint and what did his presence mean for the faithful and for the royal donor? In the New Testament, Simeon is only mentioned by Luke (Lk 2:25-35), as a man who lived in Jerusalem. It was revealed to him that he would not die before seeing the Messiah. When he finally met the Holy Family in the Temple, he recognized the Messiah in Jesus and took the child in his arms (Lk 2:25-28). According to Luke’s gospel, Simeon spoke the following words in praise of God while holding the child in his arms: “Now, Lord, you have let your servant go in peace, just as you said.” (Lk 2:29-32). These words are known as the Nunc dimittis, also known as the Canticum Simeonis. Since the 8th century, it has been part of Compline, the liturgical celebration that closes the day.45 Thus, the semantic meaning of the saint also lies in the hope for a “good death”, the peaceful acceptance of death and its interpretation as the beginning of eternal life or salvation after death.

27According to Seymour, the Venetians “deposited the body of Saint Simeon in the Church of the Virgin (Velika Gospa) which subsequently became associated with the city’s “old hospital, or pilgrims’ hospice.”46 This association is particularly plausible with regard to the Song of Simeon, as its veneration with the Nunc Dimittis invites the faithful to reflect on the acceptance of death, which precedes the beginning of life in God. In the basilica, the holy body was first presented in a stone sarcophagus (fig. 14), that according to stylistic assessment, was possibly made in the 1270s by a local artist for the laying out of the saint’s body in the Basilica of St Mary Major (fig. 15).47 There is some debate amongst scholars regarding to which extent Simeon was venerated in Zadar prior to Elisabeth’s commission of the shrine. Vidas mentions a document that is “dated 1283 and list[s] the names of 101 noblemen from Zadar [that was] found, according to some sources, in the stone sarcophagus during the translation of the relics in the seventeenth century […]”48 The authenticity of the document is up for debate. Thus, some scholars, especially Giuseppe Praga, have emphasized how little evidence of a cult of Simeon there is in the city regarding the fourteenth century. “This forces the question of why in 1377 Elizabeth felt compelled to have built a sarcophagus to care for the neglected body of this particular saint, when the shrines of the more important patron saints, Anastasia and Chrysogonus, needed repair?”49 Therefore, it is safe to state that St. Simeon was known to some at least while his relics rested in the stone sarcophagus of the thirteenth century, and that the Queen’s donation of the silver shrine helped to establish a cult for the saint by offering a precious casket that could be opened on special occasions. Perhaps she was trying to link the cult of the saint with the independence from Venice achieved in 135850 - which is depicted in one scene of the shrine - and to stage the saint as the patron saint of Angevin rulers.

Fig. 14 a: Two Bronze Angels by Francesco Cavrioli holding the Shrine of Saint Simeon, 1647, Zadar, Church of Saint Simeon.

Photo: Mandy Telle 2022.

Fig. 14 b: Two Bronze Angels by Francesco Cavrioli holding the Shrine of Saint Simeon, 1647, Zadar, Church of Saint Simeon, photo: Živko Bačič.

Source: Archdiocese of Zadar; STANKO KOKOLE, op. cit., p. 110, fig. 1.

Fig. 15: Slap of the Stone Sarcophagus of Saint Simeon, 1270s, Zadar, Benedictine convent of St Mary.

Photo: Mandy Telle 2022.

28The queen’s motives for donating a monumental golden shrine for the remains of St. Simeon in Zadar are implemented on the one hand by written sources, as the donor’s inscription on the shrine and the contract. On the other hand, the shrine’s pictorial program sheds further light on her possible motives. The contract of 1377 informs about a visit of Queen Elisabeth in Zadar, where she saw that the body of the saint was not appropriately deposited, and she decided to give the saint a more dignified casket: “Because our most noble princess and natural mistress, Lady Elizabeth, by the grace of God Queen of Hungary, Poland and Dalmatia and wife of our aforesaid glorious Lord, the King of Hungary, moved by the Divine Spirit, wished to visit the body of St Simon the Just, which is in her faithful city, and having seen, moved by humble compassion, that it was not resting as it should, therefore, upon her return, she sent the city of Zadar 1000 marks of silver to have a silver shrine made for the same most holy body of St Simon the Just, in which the said holy body would be buried and preserved.”51 It was not uncommon that royalty issued a more elaborate shrine for a saint. For example, the chronicler Thomas Wykes (b. 1222) stated that King Henry III (1216-72) “grieved that the relics of Saint Edward were poorly enshrined and lowly, resolved that so great a luminary should not lie buried but be placed high as on a candlestick, to enlighten the church.”52 The shrine does not exist anymore.

29While the Zadar contract implies Queen Elisabeth’s intention and plan, the inscription panel on the shrine emphasizes the fulfillment of her vow: “Here, in this chest donated by the mighty, illustrious, and exalted Elizabeth the Younger, Queen of Hungary, in fulfilment of her vow, rests Simeon the Just, who held Jesus, born of the Virgin, in his arms. Peace.” The wording of the shrine inscription and of the contract differ in one aspect. Only the contract mentions her with all her titles (“our most noble princess and natural mistress, Lady Elizabeth, by the grace of God Queen of Hungary, Poland and Dalmatia “) and as being the “wife of our aforesaid glorious Lord, the King of Hungary”, without giving the name Louis I of Anjou. The inscription on the shrine is restricted to epithets and a shorter version of her titles, namely “the mighty, illustrious and exalted Elizabeth the Younger, Queen of Hungary”. The wording in both cases is a result of careful consideration of the intended audience to whom the content would be visible. The contract needed to be known to the individual parties involved in it. The inscription panel on the shrine was meant for a broader, more public audience, to be visible for believers venerating the saint. While the iconography and images of the shrine communicate directly with all viewers, including the illiterate, the inscription is written in Latin – “the institutional language of contracts, politics, and official decrees”.53 This means that also illiterate visitors would have known that the inscription panel held highly official information on the shrine as the institutional language and size of the letters ostentatiously demonstrated her authority, but subsequently, only a literate person could decipher the meaning of the words in order to commemorate the Queen’s deed and perhaps to include her name in prayers.

30Elisabeth’s husband is visible on the shrine’s pictorial program through his likeness in one scene, and through his coat of arms. However, only Elisabeth herself is mentioned in the inscription panel. This circumstance implies that donating the shrine was her own personal project and accepted by her husband. By donating a monumental shrine, Elisabeth joined the ranks of other European royal founders and thus legitimized her own reign, in which she, as a woman, was not inferior to the ruling male elite. Therefore, it is also fitting that the inscription describes her as “powerful, illustrious, and exalted”. Some researchers have theorized that Elizabeth entrusted Saint Simeon with an endowment precisely because, as the bearer of Christ, he was supposed to answer her prayers and hopes for a male successor, which she was not able to conceive in seventeen years of marriage.54 However, Marina Vidas was able to make a credible case that the pictorial program, especially the scene that depicts Elizabeth and her three crowned daughters kneeling beneath the shrine, rather points to the fulfilment of her royal duties than to her shortcomings: by the time the shrine was commissioned in 1377, she had managed to marry her three daughters into important European dynasties.55

31Another pictorial hint to the motivation of donating the shrine lies in the scene that can be read as the death of Elisabeth’s father, ban Stjepan II Kotromanić of Bosnia. Saint Simeon gently places his hand on Stjepan’s head. On the right-hand side, either Stjepan’s nephew Tyrtko is depicted twice, or the two figures represent Tyrtko and his brother.56 The year 1353 was decisive for the various political developments in which Elisabeth was involved. Her father died, succeeded by Tyrtko, and Elisabeth married into the House of Anjou. Hence, the strong political ties between the two royal families become visible, all with the blessing of St. Simeon. It is unclear whether the young woman in the scene with open hair and a facial expression of despair is Elisabeth herself or another female family member. If it is indeed the Queen, she is depicted in an unusual way without regalia, maybe as a means to allude to her vulnerability and to invoke the sympathy of the beholder. In any case, the bereaved family is shown under the protection of St. Simeon, emphasizing thus that the members were orthodox Catholics. It is reasonable to conclude that the inclusion and depiction of this scene was particularly important to Elisabeth for socio-political and strategic reasons because the Bosnian rulers were often accused of Albigensian heresy.57 Hence, Elisabeth wanted to win the favor of the citizens of Zadar for the dynasty she represented and to oppose dualistic currents of those who did not believe in saints and miracles, as well as in particular accusations of her father’s heresy or toleration of it.58

32By promoting the cult of Saint Simeon, Elisabeth not only recognized the importance of medieval relic veneration, but also sought to authenticate the body of the saint kept in Zadar as the true body of Simeon through a new magnificent casing against other places where relics of Saint Simeon were kept, such as the one in St.-Denis, an arm relic of Simeon which, according to legend, originally fell from Constantinople into the possession of Charlemagne in Aachen and was given to St.-Denis by Charles the Bald in the ninth century, or in which the cult of the saint was propagated in other forms, as in the San Simeone Grande in Venice. At the same time, the city of Venice claimed to possess the true body of Simeon.59 None of these caskets dedicated to the saint are made in the dimensions of the Zadar shrine or with such a generous quantity of precious metal. To contest those claims, the donation of the Zadar tomb-shrine, the identification of the relics by inscription and the visual program as well as the possibility to open the shrine to present the incorrupt body of the saint, also signaled the recognition of the authenticity of the saint’s body and hence, the key role of Zadar as the repository and final resting place of St. Simeon. “Additional evidence authenticating the relics is provided by three scenes on the shrine depicting nobles or clerics attempting to steal the entire body or parts of it. These images suggest that the relics were important enough to be desired by persons inside and outside the community.”60 Subsequently, the donation of the shrine contributed not only to Elizabeth’s goal of gaining the goodwill of the municipality of Zadar for her own salvation, but also to pacify the people with the ruling dynasty to which she belonged. Hence, Elisabeth’s reasons for donating the shrine can be summarized as oscillating between political, social and religious aspects.

The presence of the goldsmith in his work: Francesco da Milano

33Apart from his involvement in the making of the shrine of St. Simeon, we can reconstruct much about Francesco da Milano. In 1983, Petricioli mentions 25 contemporary sources about him in the State Historical Archives in Zadar and by hand, Giuseppe Praga transcribed some of them and six more that are not mentioned by Petricioli. These transcriptions are now in the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana in Venice.61 We learn about property purchases and sales, the hiring of apprentices, journeymen and servants, a legal dispute with another goldsmith and much more.62 However, these sources do not reveal Francesco’s date of birth or death. He is first mentioned in Šibenik in 1359 as a subject of Ban Nikola Seč, who asked the Venetians to compensate Francesco for confiscated goods. There is no reference to Francesco’s profession in this source.63 His reasons for settling in Zadar are unclear. Where did he grow up? His father is mentioned in the sources as Antonio da Sesto, while Francesco is mentioned in sources as da Mediolano, from Milan. Was his father a goldsmith and did he settle in Milan? Was Francesco apprenticed to another Milanese goldsmith? What were the conditions for a goldsmith in Milan, and did he have to come from a well-heeled family? Is the fashion for stubble beards on the shrine a clue? Was the competition in Italy too fierce? Did he follow a commission to Zadar? Did he marry into a family of goldsmiths in Zadar and was able to take over the workshop of a goldsmith based in Zadar after the death of his father-in-law, as was permitted in other cities?64 According to older literature, Francesco da Milano seems to have left Zadar around 1400, which can be deduced from the numerous property sales at this time. The last document Petricioli knows is from April 1400.65

34In 1999, Emil Hilje was able to find over fifty additional, previously unpublished sources on Francesco da Milano in the State Archives in Zadar, which hold information on the last years of his life. According to these sources, the goldsmith left Zadar in 1397 to move to Nin, as he appears as a witness in a document from June 1400, where he is mentioned for the first time as a citizen of Zadar and resident of Nin.66 Hilje speculates whether the older master settled in Nin due to competition from younger goldsmiths in Zadar when his work ceased to develop. The last mention of Francesco dates back to June 1400 and he seems to have settled in Zadar again.67 This means that currently, over eighty written sources on Francesco are known. As numerous as these documents are and inform about his life, his financial circumstances, his workshop employees and household helpers, they reveal very little about his confirmed works beyond the shrine for St. Simeon. Therefore, some researchers attributed further goldsmith works from Zadar and Nin to Francesco according to stylistic criteria.68 This suggests that perhaps not every commission required a written contract. Some orders might have been commissioned verbally directly in the workshop, and it is possible that Francesco himself kept an account book in which he recorded donated, purchased and sold goods. Since no such account book is known, this consideration must remain in the realm of speculation. A large royal commission, which not only required much more precious material but also a longer production period, demanded a written contract for any security deposits, penalties for misappropriation of materials etc., and since the artist did not work at court, where the patron could regularly supervise the commission herself and request modifications directly, the contract provided additional security and controlling measures.

35Several documents in the Zadar archives inform us that Francesco employed a few assistants during the complex creation of the work.69 This is consistent with the other surviving contracts, for example for the Gertrude shrine of Nivelles and the shrine of Saint Germain des Près.70 On another account, Matthew Paris informs the reader that several artisans from London were involved in the making of the Edward shrine for Westminster Abbey in the thirteenth century.71 While the names of the goldsmiths from London mentioned in the plural form, are unknown, many names of the involved goldsmiths from Zadar are documented.72 This reinforces the assumption that it was a common practice that several goldsmiths and craftsmen could be involved in the genesis of such a large-scale goldsmith work that took several years to be accomplished. With several artists involved in the work, the completion and continuous work on the monumental shrine could advance more effectively because it required different skills, which perhaps one master could not manage alone, especially within the short duration of one year as the contract for the shrine of St. Simeon demanded. Regardless of how many hands were involved in the completion of the shrine, in the end only Francesco is mentioned as the contractor and in the inscription. This indicates that he was the responsible contractual partner and thus, likely the only artist who was eligible for both an inscriptional and pictorial presence on the shrine.

36However, as detailed as the contract is, critical questions remain unanswered. There is no specification for the inscriptions mentioning the queen and the goldsmith. It is a paradox, because the inscription is clearly visible and legible on the shrine. Was it possibly integrated into the preparatory drawing? Was it a verbal agreement? Who wrote it? Furthermore, there is no mention of Francesco being allowed to hire helpers, which he did, as documents in the Zadar archives prove.73 Even if several hands were involved in the production, only the master goldsmith was worthy of a contract. He alone was responsible and liable for the success or failure of the endeavor, so only his name was eligible of a signature on the shrine itself. Although the contract makes no reference to where the shrine was to be made, we can assume that this was done in Francesco’s own workshop, under frequent supervision by the Queen’s nobles.

37As the contract contains neither a commission for the donor’s nor the artist’s inscription, we must speculate as to why these inscriptions are nevertheless found on the shrine. According to Tobias Burg, signatures are the most important argument for attributing a work to an artist.74 They are an expression of an artistic self-image, the artist’s pride, pragmatic economic considerations and his or her status (depending on the client).75 In the case of Francesco’s shrine, these considerations summarized by Burg on the function of an artist’s signature prove to be true. A certain pride on the part of the artist is suggested by the signature in the immediate vicinity of the royal patron. Both depictions of the artist, the pictorial and the written one, frame the donor’s inscription, as if to convey that without the artist’s hand, the body of St. Simeon and the wishes of the royal patron could not have been translated into the visible material reality of this precious shrine. It is certainly to Francesco’s credit that he worked on behalf of the royal family, which inevitably had an impact on his status as a goldsmith and artist. However, a royal commission does not always mean (at least when we look at other surviving signed goldsmiths’ works) that an artist was allowed to leave his signature on them. Royal commissions could contain artists’ signatures, such as the former antependium of King Garcia III of Navarre (died 1054) and his wife Stefania that was signed by the goldsmith Almanius76; but to the best of my current knowledge, no other royally commissioned shrine, for example the shrine of St. Edward in Westminster, bears artists’ signatures.

38Hence, there must be further reasons as to why Francesco could sign his work. One hypothesis is that he wanted to share in the saint’s miraculous deeds and tied his hope for his own salvation to St. Simeon after his death. His self-portrait is framed by two miraculous healings and is located on the sloping roof opposite the figure of the reclining St. Simeon. Francesco’s piety and concern for his salvation are reflected in his will, which he wrote on April 16, 1388 in light of a sea voyage to Venice and possible related complications when travelling by sea.77 The will documents Francesco’s wife Margarita for the first time, whom he appointed as his universal heir and who was also to provide “for the salvation of the soul of the same testator” in a kind of reciprocal relationship of give and take.78 The will states that he made donations to various churches for his soul: “Firstly, he stipulated that a silver chalice worth and costing 16 gold ducats be donated to the church where the body of the same testator was to be buried. He also bequeathed twelve small pounds for his soul to the nunnery of St Nicholas in Zadar. He also bequeathed a double wax candle worth one ducat for his soul to the church of St Stephen in Zadar. He also bequeathed a double wax candle worth one gold ducat for his soul to the chapel of St. Simeon the Righteous in the church of St Mary of the Priests in Zadar.”79

39Coming back to the shrine itself and Francesco’s self-representations, it can be stressed that the community of Zadar should be reminded by Francesco’s self-reference whom to thank for the precious shrine they came to see over a long period of time, even transcending Francesco’s death and reminding the community to include his name in their prayers.80 In this case, artistic pride and artistic humility are not mutually exclusive: As Francesco is depicted kneeling before the shrine in a gesture of modesty (fig. 16), the concept of the artist’s humility resonates. This is supported by the fact that the artist’s signature appears in a single line and is subordinate to the pompous inscription of the patron. But simultaneously, his signature in a single line forms the visual base for the donor’s inscription, and what Ulrike Bergmann so aptly said about no art being possible without a donor needs to be extended to the statement that there would be no monumental shrine without the work of the goldsmith.81 It is this very intersection and social entanglement that enabled the goldsmith Francesco da Milano to capture his own likeness and name on a precious artefact that displays the royal donor in name and image, as well.

Fig. 16: Francesco da Milano, Tomb-Shrine of St. Simeon, dated 1380, backside, detail: Self-portrait of the goldsmith, Zadar, Church of St. Simeon.

Photo: Mladen Grčević, source: Marijan Grgić, Der Gold und Silberschatz von Zadar und Nin, Zagreb: Turistkomerc, 1972, p. 121.

40Pragmatic economic considerations may also have contributed to Francesco’s activity. The signature represents a unique selling point for the artist, which could attract potential new customers. Another aspect that Burg does not mention, but which I suspect is present in other signed works by goldsmiths, is that the signature demonstrates the successful transfer and fulfilment of a contract. Following that thought, a parallel can be drawn between the Queen who vowed to erect a shrine for the saint in the contract, while the donor’s inscription on the shrine itself testified to the fulfillment of her vow, and in the same way, the goldsmith promised by contract to make that shrine and analogous to the donor’s inscription, the artist’s signature testifies for the fulfillment of the goldsmith’s responsibilities. In the case of the shrine of St. Simeon in Zadar, the names were displayed in a sacred space which was not only accessible and visible to the faithful but also on an extended, metaphysical level, to the heavenly beholders, including St. Simeon and God himself. That means that both the earthly and the heavenly beholders were witnesses of a fulfilled legally binding vow, and could commemorate the good deeds of the Queen and the goldsmith, and include their names into their prayers for their souls.

41Why was Francesco commissioned with the royal enquiry? Was he the better goldsmith for the shrine? This question cannot be answered from the surviving written documents. The contract for the shrine gives no indication as to why Francesco was given the commission. Therefore, we can only speculate about the answer. In my opinion, the awarding of the contract may be linked to Francesco’s network and organizational structure. Another function of Francesco’s signature is the goldsmith’s motivation to demonstrate his own artistic knowledge, his network and value, which can be compared with that of other preceding masters who were often received in Francesco’s time, some of whom to which he alludes in his own work.82 Francesco thus adapts the Presentation in the Temple by the famous Florentine master Giotto. However, Francesco does not copy verbatim but rather translates Giotto’s pictorial solution from the fresco into his own field of expertise, namely goldsmithing. He simplifies some forms and, in contrast to the fresco, emphasizes others more prominently from the material background as bas-reliefs to heighten the effect.

42It should also be noted that Francesco is not the only goldsmith associated with the city of Milan who is represented both in writing and image on a precious monumental reliquary he made. More than half a millennium before him, the master Wolvinus created a magnificent gold altar for the church of Sant’Ambrogio in Milan. It was commissioned by Angilbert II. Both the patron and the goldsmith can be found on this golden altar, inscribed and depicted on the back of the monumental work in a medallion facing east, towards Jerusalem, in the apse of the church. On the Milan golden altar, both the patron and the artist are crowned by St Ambrose (fig. 17).83 Although the goldsmith kneels before the saint, his coronation by the saint represents such an immense honor that the scene invokes the critical question of whether we can still speak of the concept of “artist’s humility”; or, as Horst Bredekamp assumes in relation to medieval artists’ signatures, it rather reflects artistic pride and a form of “affected humility”.84 Ivan Foletti analyzed the Milan altarpiece with regard to its iconography and the deeper semantic meaning of the written and pictorial inscriptions of patron and goldsmith. He came to the plausible conclusion that the relationship between either Moses and Besaleel or Besaleel and Olohiab may have been intended.85 A comparison to the self-portrait of Francesco da Milano in Zadar likewise shows the goldsmith in a kneeling position before the shrine, and hence before St. Simeon. It is not known whether Francesco saw the Milanese golden altar, but his or his family’s Milanese origins and his profession as a goldsmith suggest the possibility. The fact that Francesco worked from a depiction of Giotto to create his scene of the presentation of Christ in the temple suggests his affinity for emulating or being inspired by well-known and circulated models or famous pictorial solutions. The contract for the Zadar shrine does not mention any models. It therefore seems plausible that these sources of inspiration, Giotto and Wolvinus, were either seen by the artist Francesco da Milano himself or handed down to him in drawings and copies that were available to him.

Fig. 17: Wolvinus and workshop, the goldsmith Wolvinus (lower right medaillon) and the donor Angilbertus II. (lower left medaillon) are being coronated by St Ambrose, c. 840, Milan, Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio.

© Domenico Ventura

43This hypothesis can be taken further by analyzing the other sources of artistic inspiration used by Francesco da Milano, especially regarding his self-portrait. For example, it is worth considering whether Francesco’s self-portrait with a stubbled beard poses a pictorial metaphor for his hard, barely uninterrupted work on the shrine, over which he perhaps occasionally forgot about personal hygiene, and thus ennobles his eagerness to perform both in the service of the Queen and in the service of the sacred sphere. On the other hand, it could also be a common fashion among Zadar men, or men from certain circles, as Francesco is not the only figure with such a beard on the shrine. At this point, further research into his physiognomy is necessary, comparing his portrait with contemporary works, which are probably more likely to be found in Italy, where portrait art was developing in an exemplary manner at this time and oscillated between medieval stylization and individuality in the transition to the Renaissance. This study also includes an analysis of his self-portrait in back profile and with a sideways glance, in which the goldsmith shows that he is not inferior to other artists of the time. For instance, Filarete’s signatures and self-portraits on the bronze Portale del Filarete in St. Peter’s in Rome, which he produced between 1433 and 1445 for Old St. Peter’s and which was transferred to the new church as the main portal (fig. 18).86

Fig. 18: Filarete, Portale del Filarete, detail: self-portrait, between 1433 and 1445, Rome, St Peter.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Porta_del_filarete,_autoritratto_con_firma.jpg (12.02.2024).

44One portrait shows Filarete in side profile in a portrait medal, another in a frieze on the back of the left wing shows him striding with a sideways glance, a compass in his left hand and in a work coat in the company of his pupils, celebrating the completion of the work with wine and dancing to musical accompaniment. It is obvious that Francesco da Milano was not unfamiliar with such depictions. The reference to the preliminary drawings on cotton paper in the contract for the shrine of St. Simeon proves that such preliminary drawings based on tried and tested pictorial solutions circulated in workshops. Was Francesco simply picking up on a tradition that had already proven its worth in Italy?87 Surely the patroness must have agreed with Francesco’s signature – Does Francesco’s employment reflect the artistic taste and understanding of the Angevin rulers, placing them among other leading European houses that supported skilled artists? In a sense, however, it also shows that an Italian goldsmith was appropriated by a non-Italian family. We do not know why exactly the Queen commissioned Francesco da Milano, we can only speculate about the reasons. Was it due to his origin and the possibility that he might have had a wider-spread network and skillset than other local goldsmiths? Did he have a vast knowledge of different artistic skills and was possibly known for a certain ability to adapt forms and pictorial solutions of known Italian masters and other artists better than other goldsmiths of Zadar? Did he have the space, that is a big enough and well-equipped workshop, as well as the knowledge of how to run a large-scale and time-consuming project that required involving and coordinating several and variously specialized workers? Did he enjoy a reputation of being a particularly honest and conscientious contractor? The answers to these questions still remain elusive but are fruitful starting points for future research on this goldsmith.

The Reception of the Presence of the Artist in different Settings and Practices

45Who could see the shrine, especially the self-portrait and the artist’s signature on the back? To answer that question, a digression on the places and modes of presentation of the shrine is necessary, as it was kept and presented in various sacred places in the city over time, as a direct consequence of Zadar political developments. Hence, the original intentions of the donor and goldsmith to inscribe their presence into the work itself might have undergone shifts of perception for the beholders.

46The gilded shrine of Francesco da Milano was initially created for the Romanesque Basilica of Saint Marije Velika (also known as the Basilica of St Mary of the Assumption, Velika Gospa, Sancta Maria Maior or Sancta Maria Presbyterorum). During the fifteenth and early sixteenth century it was displayed in an elevated position in the Chapel of Saint Simeon. The chapel was located at the northeast flank of the church. A church of St. Simeon next to the chapel of St Rok at the south-west of the large basilica was planned and begun in 1397, but never completed.88 In the 1570s, the basilica situated next to the city wall was demolished for the construction of a defensive fortification wall in the aftermath of the Ottoman-Venetian War (“Cyprus War”, 1463-1479). The shrine was then transferred to the sacristy of the old basilica, which was the only part still preserved. After some time, the chest was transferred to the chapel of St Rok; the Goldsmiths’ Alley also bordered this chapel. It was not until later that the shrine was given to the Benedictine nunnery of Saint Mary for safekeeping in the chapter house. Scholars have different views as to when the relics of the saint were transferred to the silver-gilt tomb-shrine. Dusa argues that the translation into the precious metal shrine happened as early as 1571, while Vidas states that the relics were placed in the shrine on May 16, 1632, and solemnly translated to the church of St Stephen (Stjepan), which was re-consecrated as St. Simeon (Sv. Šime) on that occasion.89

47Various written sources might provide information on when the body was entombed in the silver-gilt shrine according to Queen Elisabeth’s wishes when she donated the precious goldsmith work. In 1486, Konrad von Grünemberg mentions that the body of the saint was resting in the stone sarcophagus.90 This had not changed when in 1494 Pietro Casóla (1427-1507), who was on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, visited Zadar and wrote down his experience in his pilgrimage chronicle.91 Casola’s chronicle sheds light on the display of the shrine itself, his perception or memory of the inscription and certain practices in which the relic of the saint was involved in. Therefore, selected passages of his chronicle should be discussed in more detail. Together with other pilgrims, Pietro visited a church of St. Simeon, where the body of the saint was shown after the singing of vespers: “Andai con li altri peregrini, però che cossì era ordinato, ad una giesia de Santo Symeone, unde, cantato lo vespero, fu monstrato lo corpo de santo Symeone”92. Casola’s emphasis on the fact that the body was shown after the vespers were sung correlates to the role of the Hymn of Simeon as being part of the Compline, the liturgical celebration that closes the day.93 Thus, it is safe to assume that it was a custom in Zadar to sing the Nunc Dimittis in front of the relic of Saint Simeon and that the relic might only have been shown on special occasion, such as a festive day. The day Casola visited was such a festive day, where many pilgrims and citizens of the city and country came: “pero che gli era una grande furia de peregrini et anche de quili de la citade e de contato chi concurrevano perché era dì de festa”94. The author further points out that the body of Simeon is in very good condition and is not lacking a thing (“Nam se fe vede tuto integro non li manca cosa del mondo, non in el volto, non in le mane, non in li pedi”95), and that the believers offered many oblations for the saint, and touched the relic with rosaries and rings (“E lì de peregrini se facevano de molte oblatione e facevano tucare essa reliquia, con Paternostri et anelle, etc ...”96). Through touching a holy relic with other objects, secondary relics were created. In this way, the faithful were able to transfer the salvific power of the saint to their everyday prayer aids or other objects.

48The Chronicle also informs about the location in which the relic and the shrine could be seen. Apparently, Casola visited a St. Simeon’s Church, which was still under construction. Hence, he did not see the current St. Simeon’s church, but rather the one that was never completed. Upon his visit, only the choir was partially finished: “La giesia è asai bella; in el coro ha fin a X stadii, molto notabili; el coro è facto solum da una parte; ho extimato che fornirano el resto col tempo, perché ciò è facto è novo”97. Furthermore, the relic of the saint did not rest in the golden tomb-shrine, which according to the author, was placed high above the relic as an ornament (“In el loco unde è dicta santissima reliquia, egli una arca, di sopra al loco, unde è in alto”98). The source shows us that in 1494 the body of the saint was still on display in the very stone sarcophagus mentioned above, and that the gold shrine was merely used as decoration. Casola additionally gives evidence of the material, pictorial and epigraphical components of the work by writing that it was made of gilded silver with the “Presentation in the Temple” and in the center, there was a Latin inscription that mentions a Hungarian queen who commissioned the shrine: “In el loco unde è dicta santissima reliquia, egli una arca, di sopra al loco, unde è in alto; è tuta de argento, inaurata, unde gli è sculpita la presentatione de Cristo in el templo, et in mezo de dicta arca el titulo in latino, como una regina de Ungaria l’haveva facto fare.”99 It is not known why the people of Zadar acted against the explicit wishes of the donor, Queen Elisabeth, and why the saint’s remains were not in the gold shrine. One possible reason could be the accessibility of the saint’s body relic, which pilgrims wanted to touch.

49Casola reports on the inscription; still, he does not say on which side of the shrine it is located, and he does not mention the goldsmith, but rather “a queen from Hungary” (“et in mezo de dicta arca el titulo in latino, como una regina de Ungaria l'haveva facto fare.”100) who donated the shrine. It can be assumed that Casola and other pilgrims were able to approach the shrine, walk around it and see the inscription for themselves. However, the elevated position on pillars perhaps prevented the donor and artist inscriptions from being legible. If we assume that the names of the donor and the artist are mentioned in inscriptions to be preserved for posterity, then these name inscriptions had no significant effect on the pilgrim Pietro Casola, as he did not receive their names for posterity, only the social status of the donor. It should be kept in mind that Casola’s writing is a pilgrim’s account that concentrates more on the visit, the furnishings and practices in religious settings and accumulates a “who’s who” of the sacred remains and places that a pilgrim could see with his own eyes, boast about while simultaneously profiting from their effective power for his own salvation. Hence, to him the inscription panel was important insofar, as it represented the titulus for the shrine that provided an explanatory text and legitimized the reliquary’s value and subsequently, the relics’ authenticity.

50As late as 1569 the relic was not kept within the shrine, according to the travel report of Ludwig von Rauter, who saw the stone sarcophagus where Simeon’s body was kept and next to it, the shrine made from precious metal, elevated on four columns made of stone.101 The elevated presentation of the shrine was already alluded to in the contract between the queen and the goldsmith, as the legal text also provided for the gilding of the underside. It is not clear from the various sources at what exact height the shrine was erected, but it can be assumed that it might have allowed the visitors to walk or crawl underneath. This should have brought them as close as possible to the body of the saint - provided that his body would have been placed inside the shrine - and the miraculous power attributed to him. This practice of crawling under a shrine can be attested for the shrine of St. Edward in Westminster Abbey before it was given a new base. A vita of St. Edward from the middle of the thirteenth century (or a little later) contains miniatures showing Edward’s shrine before the renovations: the shrine was in an elevated position and depicted miracles that are said to have emanated from the salvific effect of the saint’s bones.102 The devout would have crawled through a tube in the base of the shrine while a priest sang a Te Deum.103

51Another common medieval practice in which shrines could be involved were processions.104 It is not known whether the shrine of St. Simeon was regularly carried in processions, but there must have been a solemn procession at the latest in 1648 when it was transferred to St. Stephen’s Church, which was renamed St. Simeon.105 Since the shrine was transferred there, apparently only priests were allowed to see the back, according to Josip Lenkić.106 In this case, the donor and artist inscription could have been visible to the priests and occasionally to other visitors allowed behind the shrine. They could have included the names of the donor and goldsmith in their prayers and thus prayed for their salvation.

52Furthermore, as the imagery of the shrine suggests, especially in the scene on the top left on the back of the pitched roof, the tomb-shrine might have played an important role in swearing oaths on the relic, a common practice in the medieval period. For example, the Bayeux Tapestry from the eleventh century depicts Harold Godwinson swearing a solemn oath of allegiance to William of Normandy on holy relics by touching with his right hand a portable altar and placing his left hand on a reliquary that stands on an altar (fig. 19).107 But one need not search that far away from the shrine of St. Simeon and the city of Zadar for references to the medieval practice of swearing oaths on relics. In the very city, citizens swore their loyalty to Queen Elizabeth and King Louis I. of Anjou on the arm reliquary of St. Chrysogonus in 1392.108 Not only were solemn oaths amplified by the power of holy relics, but breaking such a solemn oath could be punished by the same saint’s relics, as a scene on the shrine possibly depicts a man being struck down and falling to the ground in the left side of the panel, where he previously seemed to have taken an oath on the right side (fig. 19).109 It means that the saint’s shrine was not only a precious reliquary for the veneration of Simeon’s bodily and miraculous remains, but also embodied political and legal power.

Fig. 19: Bayeux Tapestry, 11th century, Harold swearing an oath on holy relics to William, Duke of Normandy, Bayeux Museum.

Source:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bayeux_Tapestry_scene23_Harold_sacramentum_fecit_Willelmo_duci.jpg (12.02.2024).

53To this day, the saint is venerated there by the faithful in a lively liturgical practice, especially every 8 of October.110 Pilgrims and believers climb the stairs from the right to the top to contemplate and pray on the landing in front of the open shrine. They then go down the stairs on the left and gather in the choir between the altar and the shrine, while facing the latter, and sing the hymn of St. Simeon, the Nunc dimittis.111

Fig. 20: Francesco da Milano, Tomb-Shrine of St. Simeon, dated 1380, backside, detail: The fall of an oath-breaker, Zadar, Church of St. Simeon.

Photo: Mladen Grčević, source: Marijan Grgić, Der Gold und Silberschatz von Zadar und Nin, Zagreb: Turistkomerc, 1972, p. 115.

Conclusion

54The shrine linked the cult of St. Simeon to the city of Zadar on the one hand, and to the Angevin rule on the other hand. are deeply intertwined with the sacred and secular spheres, as well as with social, political, and artistic motivations. These connotations were made possible by the art of Francesco da Milano, a secular goldsmith, who was both deeply religious and proud enough to leave his name and image on a monumental golden shrine, contributing to the creation of a discourse on concepts of artistic signature practice.

55It is a lucky case to be able to not only analyze the work of the goldsmith but also the still existing (though fragmented) contract. A few dozen documents in the Zadar archives shed light on the goldsmith Francesco da Milano – it seems to be fruitful undertaking to trace his life and work and motivations. Yet, all these documents do not shed light on the reason why Francesco could sign the shrine of St. Simeon. In a way, though Francesco is well-document, the motives of the goldsmith seem to be elusive. We can only assume that the signature was piously motivated to near his name close to the salvific relics of the Saint to secure his own salvation – his will testifies that he donated candles to a church for his own soul - “Pro anima ipsius testatoris”112, so the shrine must have had a similar function to Francesco. Furthermore, an aspect of pride and humility the same time lies in leaving a signature under the name of the illustrious royal donor: Francesco might have left his name because he was proud to work a royal commission. But he also knew his place – visible in the one crowded line including his signature underneath the lengthy donor’s inscription. This paper – to my knowledge – assumes also an aspect of signatures that was not yet elaborated in this field: Might the inscriptions stand for the legal fulfilling of a written or oral contract? Oftentimes, goldsmith masters worked on big commissions with their workshop – and more often, only the master’s name – if any – can be found on the work as a signature. He alone was responsible for fulfilling the contract. Not only the queen fulfilled her vow to donate a shrine for St. Simeon, but also the goldsmith stayed true to the commission. Can we even interpret the inscribed names in the inscriptions in such a way?

56The shrine itself with its written and pictorial program, the existing contract, the people involved in its production and the pious performative acts in which the artefact was involved, all followed motivations that were intended to create a timeless presence in history, with the aim of a permanent commemoration of both Saint Simeon and those involved in the genesis of the work by the viewer. The shrine of St. Simeon thus represents a mirror of Medieval society and the various artistic, political, and religious networks that extended beyond the coastal Dalmatian town of Zadar. In the same time, the shrine documented the presence of the artist Francesco da Milano, transcending his death.

Annexes

Contract for the production of the gold shrine for St. Simon Iustus in Zadar, 1377113

(Conpositionis) pro archa (argentea sancti Simonis fabricanda per magistrum Franciscum aurifficem.)

Suprascriptis, millesimo, indictione et die dominica, (quinto) mensis iullii, regnante, ut supra. Cum illustrissima principissa et domina nostra naturalis, domina Helisa(bet,) Dei gratia regina Hungarie, Polonie (et) Dalmacie et gloriosi dicti domini nostri regis Hungarie consors, divino spiritu (com)ota, visi(tare) (vo)lui(ss)et corpus beati (Simonis Iusti, in) sua fidelle civitate existens, quo viso humilli compassione comota non iacere, (ut) (convenien)s (e)st, (i)dcirco Jad(ram) (post recessum suum) (destinav)it mille marcas argenti causa ipsi beatissimo corpori sancti Simonis Iusti fab(ricandi) (arcam) (u)nam arg(enteam), (in qua dictum corpus sanctum) (re)ponetur et conservetur, ut dictum est, et pro dicto opere cicius conficiendo idem domina, (regina nostra, per) (sua)s g(enero)s(as) (literas) s(cri)psiss(et) (dillecti)s fidelibus suis Jadriensibus, dominis Francisco de Georgio, Mapheo de Matafaris (et) P(aulo) de G(eor)gio, strenuis (militibus regiis,) (ac) ser Grixogono de Cevalellis et Francisco de Cadulinis, ut ipsi, prout cicius fieri poterit, (dictum opus) perfic(iatur.) (Qui) s(tr)e(nui) (milites,) (dominu)s Franciscus, dominus Mapheus et dominus Paulus ut fidelissimi regie maiestatis, (tam suis nominibus quam) nominib(us) ser Grixogoni de C(eva)l(ellis) (et) ser Francisci de Cadulinis, qui absentes erant, cupientes benigne regia (man)d(ata) p(ro) posse (adim)plere, s(e) reg(io) (n)o(m)i(ne) (convenerunt) (c)um magistro Francisco aurifice quondam Antonii de Mediolano nunc habitatore Jadre, pro dicto opere conf(ici)end(o)(,) (hoc) (m)odo (videlicet), quod dictus (magister) (Franci)sc(u)s (s)e solempniter obligando prescriptis strenuis militibus nomine, quo supra, solempni stipulatione promisit et se obliga(vit) e(isdem) d(ictum) (o)pus s(ive) (dictam cistam) (ar)g(enteam) bene, fideliter et legaliter, omnibus malicia et fraude postpositis, facere, operare //

et exercere hinc ad (unum annum) p(roxime) v(enturum) d(e) (bono et puro) (ar)g(en)to, q(uod) (ei per) (vir)os (n)ob(iles)(,) ser Iohannem, ser Gall(i) (et) ser B(artulum) d(e) (Cipriano, omnes) ci(ves) Jadrienses, quibus dictum argentum (totum in) (c)ust(o)dia d(atum) es(t) a(d) cons(ervan)dum, dabit(ur), et de illa liga et b(onitate) (argenti ad illam formam) et (similitudinem) dicte arche argentee conficiende (et) cum illis formis, ymaginibus, si(gni)s, (mi)r(a)culis et presentati(one) (domini nostri Ihesu) Ch(risti) (presentati) ad alt(are), pro(ut) est qued(am) arca (in carta) bumbici(na) d(ata) (et facta) ad similitudinem dicte arche arg(entee) conficiende, que figure (omne)s (relev)ate (esse) deb(ent), (ut conveniens) (er)it, et (dictam arcam) (intu)s et ex(tra) et desup(er) (et) (d)e subtus (in)d(aurare) deb(et) per (t)o(tum) (cum) omnibus (i)l(li)s fig(uris)(,) (que) (in)d(auran)de e(run)t(,) (et ut) dic(tum) op(us) perf(iciatur)(,) dictus magister Franciscus solempni stipulatione promisit et se obligavit (dictis strenuis) militibus (regiis) [et eis promittens]114 ad conficiendum dictum (opus)(.) Que omnia et sing(ula) sup(rascripta) pro(misit) quo(que) dictus magister Franciscus stipulatione solempni dictis stre(nuis) militibus stip(ulantibus) (et) (reci)p(ientibus)(,) (ut supra, attendere, observare et adimplere et non contrafacere vel -venire) aliqua ratione vel (causa, modo vel) (ingen)io(,) (de iure) vel de f(acto)(,) sub pena (quarti valoris predictorum, tociens comittenda et cum) (e)ff(ectu) exig(enda)(,) (reiterando quociens contrafactum fuerit,) pre(dicti)s (vel) aliquo pred(ictorum)(,) qua sol(uta) vel non, nichilominus contractus (i)st(e) s(uam) semper ob(tineat) (r)ob(ori)s firmitatem, et (cum) (re)ff(ectione) (omnium damnorum interesse et) expensis (liti)s et extra et cum obligatione omnium suorum bonorum presentium et futurorum. Et (dicti) (re)g(ii) (milit)es (nomine)(,) quo supra, solempni stipulatione promiserunt ipsi magistro Francisco dari facere per dictos, ser Iohannem et ser Bertolum, conservatores tocius dicte q(uantitatis) (argenti, pro unaquaque vice) (mar)cha(s) (quinquagint)a (ar)g(enti) ad laborandum aut tantum plus aut tantum minus, quantum dictis conservatoribus vide(bitur) (pro) dicto (opere) exped(ie)n(do)(,) quo labo(rato) (idem magister Franciscus) dictis conservatoribus dicti argenti ad illud pondus et tale argentum restit(uere)(,) (prout ipse) magister Franciscus h(abuit)(,) (et) si(c) (et taliter usque) (a)d f(inem) dicti operis, et totam quantitatem auri pro indaurando dictum oppus, que opor(tuna) (erit) ad (hoc)(,) cum (ea) quantitate argenti v(ivi) (ad hec necessaria, et) pro suis fatichis ducatum unum auri pro qualibet marca argenti labo(rati) per dictum magistrum Franciscum (in) dicto opere(,) (et pro arris et parte) s(olu)tionis dicti operis dare hinc ad paucos dies ipsi magistro Francisco flo(renos) ducen(tos) (auri)(,) sub pena et obligatione predictis. (Et pro) predictis (omnibus) et singulis melius attendendis et observandis sponte et per pactum dictus magister Franciscus obligavit se suosque heredes (et successores et omnia sua) bona praesentia et futura penes dictos regios milites stipulantes(,) (ut) s(u)p(ra)(,) et ad (conveni)endum tam realiter quam personaliter s(emel) et (pluries, usque) ad plenariam et condignam satisfactionem omnium predictorum Jadre, Dalma(cie)(,) (Croacie, Sclavonie,) Obrovat(ii)(,) Anco(ne)(,) (M)arc(hie)(,) (Ystrie, Foroiullii,) Venetie, Lombardie et ubique locorum et terrarum et omni tempo(re) in (quacumque curia) et coram quacumque domin(atione)(.) (Et voluerunt ipse) partes ambe contrahentes, ut de predictis ego, notarius infrascriptus, duo d(e)b(eam) (publica) (con)ficere instrumenta unius eiusd(em) (ten)o(ris) (et parti cuilibet) (tra)dere unum. Actum Jadre sub logia magna comunis, presentibus viris nobilibus ser (Sa)ladino quondam ser Chose de Salad(inis)(,) ser (Nicolao quondam ser) Grixogoni de Marino et ser Marino quondam ser Vulcine, Pe(tri) de (Mata)faris, omnibus civibus (J)ad(riensibus)(,) (testibus) vocatis, rogatis et al(iis).

[In the margins] (Ser Madius de Fanfogna, iudex, examinator)

Abbreviation

HR-DAZD = Historijski arhiv u Zadru (Historical archive in Zadar)

Primary sources, unpublished