- Accueil

- > Livraisons

- > Troisième livraison

- > A Reevaluation for the Genoese period of the Galata Tower : Epigraphy and Architectural History1

A Reevaluation for the Genoese period of the Galata Tower : Epigraphy and Architectural History1

Par Hasan Sercan Sağlam

Publication en ligne le 10 décembre 2021

Résumé

The Galata Tower has been witness to many historical events and has gone through multiple architectural phases over the course of its long life. Its Genoese origins began to receive scholarly attention particularly in the late eighteenth century and especially during the nineteenth century. In the meantime, a consensus was reached about the history and architecture of the tower’s Genoese period. However, this consensus was based on a few primary sources without any comprehensive approaches nor in-depth investigation. The tower’s erroneous name, “Tower of Christ” (Christea Turris), during its Genoese period is perhaps the most widespread assumption in the secondary literature. A first construction by Anastasios I and a heightening around 1445/1446 are further related misconceptions that all three arguments were derived from a single, though irrelevant inscription. Despite the popularity of Galata as a research topic, these misconceptions have become anonymous and continuously repeated without being questioned. Moreover, slightly different arguments for the tower were put forward. When compared to later periods of the monument, the former name of the tower, its alleged Byzantine past, and especially the Genoese architectural identity of the present structure remain rather ambiguous in the light of all the arguments in the literature. For these reasons, this article presents a fundamental reevaluation for the Genoese period of the Galata Tower through virtually all of the primary sources and a small architectural survey. This article shows that there is no solid evidence of the supposed Byzantine period of the tower; that it was named as the “Tower of the Holy Cross” (Turris Sancte Crucis) by the Genoese who built it, and its first structural alteration was probably executed by the Ottomans around 1453.

Mots-Clés

Table des matières

Texte intégral

Introduction

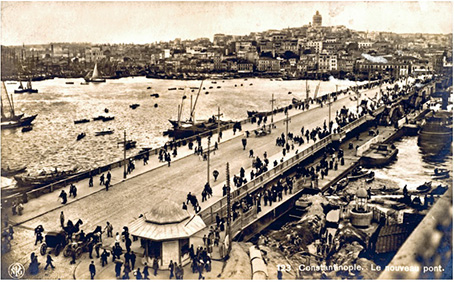

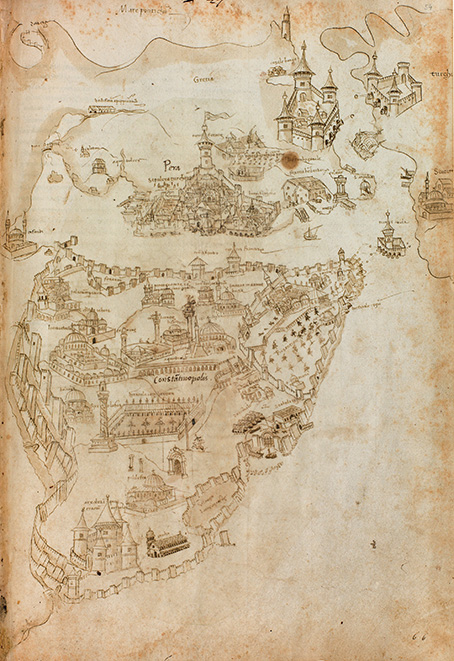

1Easily recognizable in the city silhouette with its tall and massive structure, the Galata Tower is one of the most famous historical buildings in Istanbul (fig. 1). It is located on a flat part of the hillside rising along the conical shaped topography in the Galata neighborhood of Beyoğlu district, which is on the northern side of the Golden Horn just across the Historical Peninsula. The tower stands out with its position dominating the region and its long observation range. Based on a single epigraphic source, common arguments regarding the origin of the Galata Tower emerged in the late eighteenth century. These were finalized by combining with some written and visual primary sources throughout the nineteenth century and have changed little since then. The tower has undergone many repairs and scientific studies on its architecture are generally dated to the twentieth century2.

Fig. 1: View of Galata from Sirkeci, postcard. Neue Photographische Gesellschaft (NPG), 1900s. Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation (SVIKV), IAE, FKA _00584 (see figure in original format).

2The arguments with wide public recognition, which are also cited by modern research on the Galata Tower have been repeated since the eighteenth century and have become largely anonymous over time. When all the existing academic arguments regarding the origin of the tower are taken together, the situation that emerges contains some confusion. For example, one of the most common hypothetical claims about the alleged pre-Genoese origin of the tower is that it was originally built by the Byzantine Emperor Anastasios I (r. 491–518). To the extent that this claim was rejected, it continued to find supporters. On the other hand, how it first emerged has not been clarified and a direct counterargument has not been developed in this context. The information that the tower was built in 1348 is based on reliable sources, which has been consistently underlined by several modern researchers3. The illegal construction of the tower by the Genoese has brought along a situation that has not yet been fully clarified concerning its legal status and ownership in the ongoing process. As the Genoese made a significant part of their expansion in Galata with the privileges they received from the Byzantines, considering the Galata Tower as an illegal structure has sometimes created confusion in the spatial chronology of the region. Fundamental claims originating from Eyice and Dallaway4 that the tower was repaired by the Ottoman Sultan Murad II during the Genoese period and was also raised circa 1445/1446 have not yet been examined in detail.

3In addition, there is a very common belief that the name of the tower during the Genoese period was the “Tower of Christ” (Christea Turris). According to some other sources that are in the minority, its name was the “Tower of the Holy Cross” (Turris Sancte Crucis)5. The name “Great Tower” (Megalos Pyrgos) has also been suggested after anonymous Byzantine sources6. In this case, whether the tower really had more than one name during the Genoese period and for what reason all these name arguments emerged were not discussed.

4Arguments about the architecture of the Galata Tower in the Genoese period are mostly based on the illustrations visible on different versions of Cristoforo Buondelmonti's depiction of Constantinople around 14207. Various claims about the remaining Genoese architectural phase of the tower, which was raised again by the Ottomans a year after the destruction in the earthquake of 1509 contain some deficiencies and inconsistencies in between8. Correspondingly, the tower also needs an architectural reconsideration, including its exact defensive function. Another issue that has not been emphasized much in this regard is the destruction of the tower for some reason right after the Ottoman takeover of Galata in 1453.

5After the arguments mentioned above, this article presents a detailed research and reevaluation in the light of all the relevant primary sources. Moreover, through a comprehensive and criticizing framework, it questions the modern historiography of the Galata Tower concerning the Genoese period. In the meantime, the architectural arguments for the same period regarding the present tower structure are also reconsidered and new questionings are made in this respect. As a result, it is revealed with evidence that the Galata Tower did not have a Byzantine period, to which its first construction is attributed; that it was named only as the “Tower of the Holy Cross” (Turris Sancte Crucis) by the Genoese who built it; and that its first architectural alteration was happened shortly after the Ottoman takeover, as the related structural traces on the tower also display.

The Most Important Tower of the Pera Colony

The Foundation and Expansion of Pera

6The Genoese had been trading in Constantinople since the middle of the twelfth century and they obtained their first commercial concessions in 1169. A year later, they had a commercial neighborhood called “Koparion” near the Neorion Harbor on the southern shore of the Golden Horn. This place was enlarged in 1192 and 1201 and was used by the Genoese until the Latin occupation of Constantinople because of the Fourth Crusade (1202-1204)9.

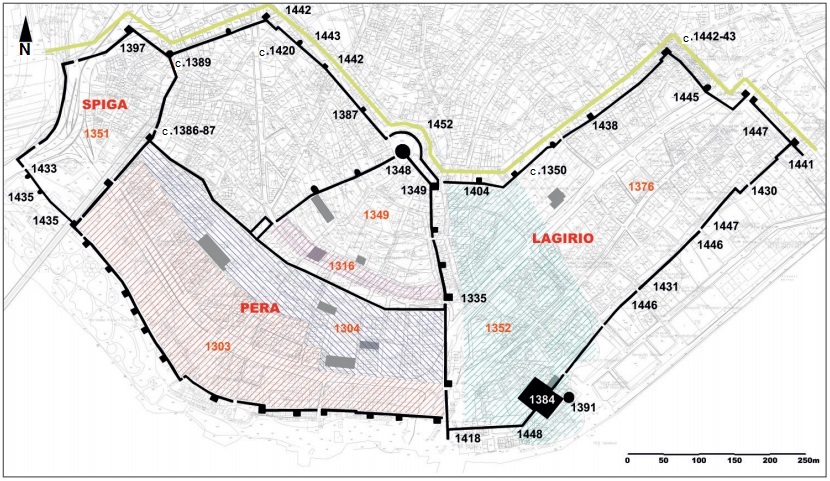

7As an indirect outcome of their alliance dated 1261 with the Byzantines against the Latin Empire, the Genoese established a commercial colony in 1267, this time in Galata on the northern shore of the Golden Horn. The colony was officially called “Pera” and on the eastern side of this defenseless neighborhood that stretched along the plain by the coast, there was a castle called “Kastellion” from the Early Byzantine Period, which secured the Golden Horn10. According to the contemporary historian Georgios Pakhymeres, Emperor Mikhael VIII Palaiologos gave the Genoese a large neighborhood extending towards the west of Galata and this concession did not include the Castle of Galata. For security reasons, he also demolished the former walls of Galata in advance11. The precise boundaries of Pera were determined by a Byzantine imperial edict (khrysoboullos) dated May 1303. This neighborhood was expanded by a second edict dated March 1304, while the first fortifications emerged in Pera when a privilege given by Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos was abused by the Genoese. Later on, the colonists expanded Pera towards the hill in the northeast. The Genoese gradually expanded their colony after further concessions and fortifications, therefore spread over a much larger area as of the fifteenth century. At this time, two lateral suburbs called “Spiga” in the west (towards modern Azapkapı) and “Lagirio” in the east (towards modern Tophane) emerged, which were adjacent to Pera and were also surrounded by walls (fig. 2)12.

Fig. 2: Pera as of 1453. Hasan Sercan Sağlam, 2020 (see figure in original format).

The Construction of the Tower After the Occupation of the Hill

8The fortifications of Pera had a keep on top of the hill. Known as the Galata Tower today, the location of this building was heavily fortified with different security levels. The tower was a vital part of the fortification system of the Pera colony, and it primarily secured the high hill that would be a great disadvantage for the coastal plain during a siege from the land side. It was naturally a long-range watchtower and was also situated directly above the main water conduit of Pera, which brought fresh water all along the main ridge. Just in front of it, there was a large semicircular barbican, protruding from flat wall courses adjacent to the tower on both sides. The position of the Galata Tower formed the main landward entrance of Pera on the main ridge with the optimum slope for transportation, where four wall courses in total intersected. In addition, a wide moat stretched before the tower as well as all along the land walls13.

9According to Nikephoros Gregoras, the Genoese intended to occupy the area towards the hill above Pera for the first time around 1335 and built some fortifications there. However, Andronikos III Palaiologos ordered those Genoese works on the hillside to be seized and destroyed14. A Genoese construction slab dated 1335, which was documented on a tower towards the hill is apparently related to this first attempt of the colonists15. Then, Gregoras further indicates that the Genoese successfully expanded their borders this time around 1348 and occupied a large, triangular area towards the hill. Afterwards, they fortified this area through a surrounding moat and strong walls and high towers16. Gregoras does not mention the construction of any specific tower but the situation in general terms.

10According to the emperor of that period Ioannes VI Kantakouzenos, the hillside just above Pera had strategic importance for the security of the colony, therefore the Genoese intended to occupy as well as to fortify it. Thus, they initially demanded this land from the emperor on the pretext of territorial insufficiency in the Pera settlement, but this demand was rejected. However, the Genoese collected uncut pieces of rock and secretly provided other necessary building materials. Meanwhile, a war broke out between the parties and at the same time, the Genoese first fortified the hill and then built a tower on its summit towards the end of 1348. They determined the boundaries of the remaining land and fortified it with a wall that they could increase as high as the construction materials they had. When they lacked materials necessary for a proper fortification, they surrounded the land with huge wooden palisades. In this way, they surrounded the entire slope in a short time. In return, the emperor ordered the Genoese to leave this newly occupied area and to demolish its fortifications. Yet, nothing happened, and the Genoese continued their insistence on the area they occupied, though also the emperor continued opposition with his army17. While these events were taking place, the war lasted until 1349 and inflicted heavy losses on both sides. Then, Nikephoros Gregoras states that during the peace negotiations in the same year, the Genoese agreed to pay a hefty compensation to the Byzantines and to return into their former borders by leaving the area above Galata that they illegally occupied18.

The Handover of the Tower Twice in a Short Time and the Fallacy of a New Concession

11In the Battle of the Bosphorus dated 1352, the Genoese prevailed against the Byzantines and the Venetians, who fought together. As a result, an agreement was signed between the parties on 6 May 135219. This treaty also included an important territorial concession that extended the Genoese quarter until the “Castle of the Holy Cross” (Castrum Sancte Crucis)20. In this regard, Desimoni, Balard and Stringa probably considered only the statements of Gregoras, therefore concluded that the castle in question was the Galata Tower. Thus, the aforesaid scholars interpreted the territorial concession mentioned in the treaty of 1352 as a Byzantine confirmation, which officially recognized the Genoese domination on the previously occupied hill, therefore also on the Galata Tower21.

12However, after the section summarized above, the continuation of Ioannes VI Kantakouzenos’ testimony reveals that the concession in the treaty of 1352 cannot be related to the Galata Tower as well as the adjacent hillside. According to the emperor himself once again, the peace talks of 1349 were initially concluded with the condition that the Genoese were obliged to leave the hill they occupied and return into their former borders. Then, they handed over the control of that newly built fortification to the troops under the command of the emperor’s son, Despot Manouel Kantakouzenos. Later, the emperor stated that he had fought not for a worthless piece of land but to demonstrate that the Genoese could not act against the interests of the empire without his consent. Convinced that he had demonstrated this determination sufficiently and that he had achieved his goal in the end, the emperor ordered his son to evacuate the region together with his army immediately. In the meantime, he ceded the hill in question to the Genoese with his own consent, by means of an edict. The outcome of the war that ended in 1349 was like this, as how the emperor of that time declares personally22. The fact that Gregoras did not mention all those critical successive events must have given rise among the scholars to the idea that the illegal status of the hill as well as the Galata Tower had continued until 1352, who seemingly considered only Gregoras for the period of 1348-1349. Hence, they superficially attributed the concession in the treaty of 1352 to the Galata Tower23. Alexios Makrembolites as another witness of that period also mentions in detail that with an imperial khrysoboullos after the war of 1348-1349, Ioannes VI Kantakouzenos officially handed over the newly built stronghold along with its illegally occupied hill to the Genoese24. A slab with coat of arms and dated 1349, which was documented on a tower just below the Galata Tower reveals that the walls along the hillside were attached to the Galata Tower only a year after its construction25.

13It appears that it was only in 1349 that the Galata Tower, which was built in 1348 through an invasion on Byzantine lands, and the triangular area that was fortified along the ridge, were officially ceded to the Genoese. In this context, on the map of Schneider and Nomidis, the year 1349 is consistent, which was written for the eventual Genoese occupation of that hilly land26. However, for other regions obtained by the Genoese in Galata, the same researchers cursorily put the years 1387, 1397 and 1400 on their map with reference to the dates of some construction slabs27. Thus, it is understood that they simply considered the slab of 1349 mentioned above, rather than the detailed narratives of Kantakouzenos and Makrembolites.

Some Testimonies About the Tower

14In a testament dated 1373, the castle and the tower of Pera are mentioned very briefly as reference points28. As of 1403, Ruy González de Clavijo reports that the walls surrounding Pera climbed to a hill and there was a large tower (torre grande) that protected the city29. In Cristoforo Buondelmonti's depiction of Constantinople, which has different versions scattered in various archives, the Galata Tower is anonymously depicted. These studies were compiled and meticulously examined by Eyice. Since there are critical architectural inconsistencies among them, depictions corresponding to the cylindrical form of the present tower structure have been put forward and the depiction in the Biblioteca Marciana (Venice) copy dated around 1420 is suggested as the most reliable version. In this depiction, the tower is noticeably higher than the other towers of the Galata Walls. The top floor protrudes through a series of blind arches, and it has crenellations as well as a conical roof30.

15The triangular fortification system of the Genoese in Galata was emphasized by Tursun Beg, who participated in the Ottoman siege of 145331. The Galata Tower was depicted with the name “Tower of the Holy Cross” (Turris S. Crucis) and with a Genoese flag on its top in the Düsseldorf copy dated circa 1485-1490, which is another version of the same Buondelmonti depiction that also shows buildings from the period of Mehmed II (r. 1451-1481)32. According to Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, there were some Genoese coat of arms and inscriptions on the tower as of the beginning of the eighteenth century33. These anonymous artifacts were seemingly disappeared in time.

A Second Symbolic Building : The Tower of the Holy Cross of the Castle of the Holy Cross

16Located on the coast of Karaköy and consisting of a rectangular cellar, the Yeraltı (Kurşunlu Mahzen) Mosque is what remains of a small castle from the Early Byzantine Period34. The Byzantines called this structure “Καστέλλιον” (Kastellion) and more anonymously “φρούριον” (fortress), to which the northern end of the chain that closed the entrance of the Golden Horn was attached against naval attacks. According to a narrative originating from Theophanes the Confessor, it was first used against the Arabs in the siege of 717-71835. During the Fourth Crusade, the Latins seized the castle that they called the “Tower of Galata” (Tor de Galathas) and then broke the naval chain36. Because of this similarity in name, as Eyice mentioned, some researchers have confused “Kastellion” from the Early Byzantine Period with the Galata Tower that the Genoese built37. The “Castle of Galata” (Castrum Galathe) on the coast was a distant reference point for the eastern border of the Genoese quarter in the Byzantine edicts dated May 1303 and March 130438.

17The Genoese captured this castle in the fourteenth century, which they called the “Castle of the Holy Cross”. This name was first encountered in the treaty dated 6 May 1352, which extended the Genoese quarter in Galata until the Castle of the Holy Cross (Castrum Sancte Crucis) in the east39. However, whether the castle was included in this concession is not clear enough in the text of the treaty. Nevertheless, Jean Froissart confirms as of 1384 that other than the city of Pera, also the “Castle of Pera” (chastel de Pére) opposite Constantinople was under Genoese control40. Later on, the Genoese added a cylindrical corner tower to the coastal side of this castle and named it the “Tower of the Holy Cross”. This structure was undoubtedly the second most important tower of Pera after the Galata Tower. Seen in many depictions from the Ottoman period, it collapsed in the earthquake of 176641.

18In the expense records of the Pera Treasure (Peire Massaria) kept in the Genoa State Archive today, there is detailed information about the castle as well as its tower with the same name. For example, on 3 December 1390, a bell was placed in the Castle of the Holy Cross, probably to give alarm during an enemy threat42. In the same year, 5000 hyperpyra was spent, this time for the Tower of the Holy Cross43. On 6 April 1391, another payment of 13 hyperpyra was made to the masters worked for the Tower of the Holy Cross44. As of 25 August 1391, the cost of the works for the “tower of the castle” amounted to 1000 hyperpyra more45. Finally, on 2 October 1391, a gilded cross above a branched pommel was placed on top of the Tower of the Holy Cross “of the castle”46. Another expense record is about a large sphere made of copper that was placed right below the aforesaid cross47. Therefore, it is understood that a cross-bearing orb (globus cruciger) as the sign of Jesus was placed on top of the tower. According to a last record of the Pera Treasure dated 1391, after its construction, the Tower of the Holy Cross was also used for storing grain, wood, weapons, and ammunition that belonged to the colony48. Confirming this, the castle appears as “arzana” (arsenal) in the Biblioteca Marciana copy of the Buondelmonti depiction from circa 142049.

19Despite all the sources mentioned above regarding the tower, it is not possible to confirm them in the Buondelmonti depictions. However, just behind the Castle of the Holy Cross, a single and roofless tower associated with the castle is regularly seen. The identity of this anonymous structure has not been fully explained50. Yet, as of the first half of the fifteenth century, this tower could only be a reverse angled and distorted depiction of the Tower of the Holy Cross dated 1391, which belonged to the Castle of the Holy Cross51. Therefore, it can be argued that the work of Buondelmonti has inaccuracies in terms of some architectural details.

The Surrender of Pera and the Fate of its Fortifications

The Destruction of the Pera Fortifications

20Doukas mentions that during the Siege of Constantinople on 28 April 1453, a warship aimed to burn the Ottoman fleet in the Golden Horn secretly at night. However, the Genoese of Pera informed the Ottomans, who stayed vigilant and then sank this ship with a cannon fire as soon as it approached52. Ubertino Posculo as one of the eyewitnesses of the siege states that the Genoese gave the aforesaid intelligence by raising a torch from the top of the tower of Galata (summa Galatae de turre)53. In addition, an anonymous Greek source copied by Theodosios Zygomalas in the sixteenth century also reports the same event, in which the Genoese of Pera warned the Ottomans through a flame over their “great tower” (μεγάλος πύργος)54. According to Giacomo Languschi as another eyewitness, whose testimonies are reached through Giorgio Dolfin, the signal flame in question rose above the city walls of Pera, in more general terms55.

21Witnessing the capture and looting of Constantinople by the Ottomans on 29 May 1453, the residents of Pera opened the gates and handed over their colony peacefully to the troops under the command of Zağanos Pasha in order to avoid a similar disaster56. Mehmed II prepared an edict on 1 June 1453 and decided on the terms and conditions of this conquest. Accordingly, the sultan promised that he would not damage or demolish the Pera fortifications57. While the expression in the Ottoman Turkish copy of the edict is directly as above, the negative suffix was added later to the relevant section in the copy of the same edict in Greek. The interpretation of Şakiroğlu for this curious situation is that there was actually a command to demolish the Pera fortifications in the first edict prepared in Greek, but those demolitions were stopped while the Ottoman copy was prepared, and the Greek text was thus corrected through a small addition58. The narratives mentioned below also reveal that some demolitions were carried out.

22According to Laonikos Khalkokondyles, Mehmed II ordered the city walls facing the land side to be demolished as a security precaution in order to facilitate the recapture of Pera in case of a possible Genoese uprising59. Likewise, Doukas states that Mehmed II had the city walls of Pera facing the land side demolished, but he did not inflict any damage on those along the coast60. Angelo Giovanni Lomellini, who was the last podestà (governor) of Pera wrote in a letter dated 23 June 1453 that Mehmed II destroyed everything; destroyed the suburbs and the moat section of the fortress; and demolished the Tower of the Holy Cross as well. Lomellini further states that the walls on the coast did not suffer any damage along with a section of curtain walls inside the barbican and the barbican section itself61. In his letter dated 16 August 1453 and written to Pope Nicolaus V, Leonardos of Chios, who also witnessed the siege states that the city walls and towers of Pera were destroyed. Moreover, the tower named after the cross as the symbol of Jesus, which was on the top of it, was destroyed until its foundations62. Lodrisio Crivelli, repeating the statements of Leonardos additionally mentions around 1460 that the tower in question drew considerable attention when viewed from the sea63. Isidoros of Kiev, who was also in the city during the siege mentions in his letter dated 9 July 1453 that the city walls and towers of Pera were demolished.64 In another letter of him dated 8 July 1453, besides repeating these, he also states that the cross on the great tower was destroyed together with the tower itself65. Quite similar statements are also found in the letters of indirect witnesses, such as of Fra Girolamo of Florence dated 5 July 1453, of Henry of Sömmern dated 11 September 1453, and of Franco Giustiniani dated 27 September 145366. According to a Venetian senate document dated 30 June 1453, cannons were used in order to demolish the walls of Pera67. In connection with all these events, a Genoese administrative letter dated 11 March 1454 emphasizes that repairing the walls and towers, evacuating the ditches, and deepening them again were necessary for the safety and welfare of Pera. In this direction, two Genoese envoys were assigned to seek an opportunity from Mehmed II68.

23According to some anonymous Ottoman historical sources that were studied as an unpublished report by Ahmed Vefik Pasha in the nineteenth century, Mehmed II demolished the Galata Tower and the surrounding walls but while the tower was shortened only 10 arşın (cubit) (approx. 7,5 m), the walls were destroyed up to 40 arşın (approx. 30 m) all around. When the sovereignty treaty concerning Pera was concluded, he did not go any further. Afterwards, Zağanos Pasha raised the tower again and replaced the cross on the top with the Ottoman banner69. This detailed quotation by Ahmed Vefik Pasha and the interpretation of Şakiroğlu mentioned above concerning the edict dated 1 June 1453 coincide in terms of partial destructions carried out by the Ottomans for a short time following the conquest. In the tahrir (Ottoman tax record) dated 1455, the towers in Galata are referred as “burgaz-i emîriyye” (sultan’s tower)70. This statement can be interpreted as an indication for the ownership of the Galata Tower to pass from the Genoese to the Ottomans.

24Despite all the destructions mentioned above, the Galata Walls were obviously not completely destroyed. They were largely present even as of the 1860s together with many characteristic Genoese construction slabs with coats of arms and inscriptions on almost every part of them (fig. 3).

Fig. 3: View of the Galata Walls and Galata Tower from the northwest. Photo: James Robertson, 1854. SVIKV, IAE, FKA_005003 (see figure in original format).

25Within the scope of the new urban planning works of the Sixth Department of the Municipality (Altıncı Daire-i Belediye) of Istanbul that was established in 1857, the walls began to be demolished in 1864 and the construction slabs were collected for display71. Based on the study of De Mas Latrie72 that documented the architectural characteristics of the Galata Walls and some of the Genoese slabs on them, Wilhelm Heyd argued that the Ottoman destructions in 1453 could only have occurred on a partial and superficial scale73. On the other hand, some researchers claimed that the demolitions of Mehmed II were a “sign of sovereignty”74. However, the testimony of Khalkokondyles demonstrates that the destruction of the Pera fortifications was a security measure against a possible uprising. In this context, it was meaningful that the Genoese ambassadors first sought an opportunity to repair the walls in 1454. As it is understood from the statements of Khalkokondyles, Doukas and Lomellini, while the fortifications on the land side excluding the barbican were destroyed to a certain extent for the security measure, the ones in the interior and on the coastline remained intact. However, the fact that the fortifications had survived almost as a whole with many Genoese epigraphic as well as heraldic traces by the nineteenth century indicates that, as Heyd suggested, the destructions of 1453 may have been quite partial. They seemingly intended to disable the fortifications instead of razing to the ground completely. In addition, it can also be said that the Ottomans may have repaired the sections they previously destroyed, just as they did with the Galata Tower. As quoted below from Evliya Çelebi, the extensive Ottoman repairs carried out after the earthquake of 1509 and then around 1635 may also have contributed to the relatively complete appearance of the Galata Walls as of the nineteenth century.

Writing the Story of the Galata Tower

A Suspicious Inscription

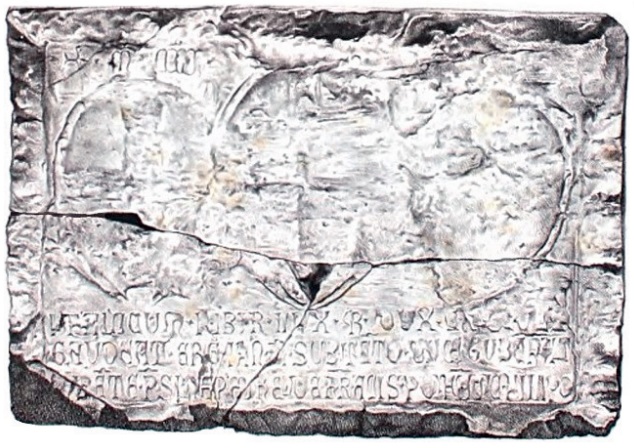

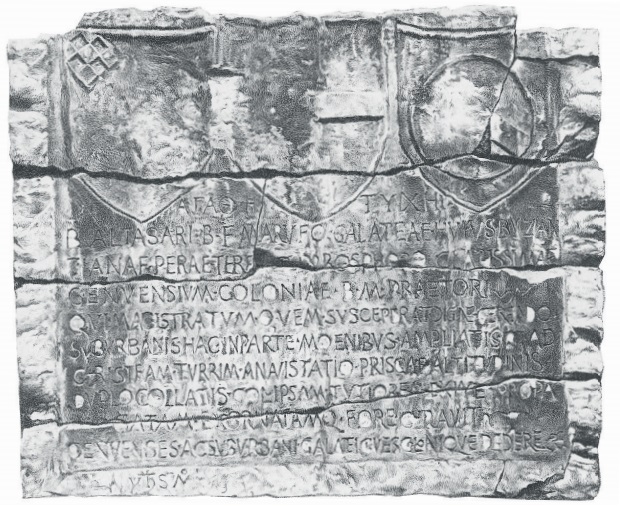

26Before the demolitions, a construction slab dated 20 September 1446 with coat of arms and a long inscription was documented above the Eğri Gate (sometimes confused with the Kireç Gate), which was the penultimate of the coastal gates along the wall course until Tophane in the east of Galata. The inscription of this artifact commemorates an important work that was carried out by Podestà Baldassare Maruffo during the Genoese period in Galata (fig. 4d). The related part of the inscription, which mentions the work in question is as follows: “SUBURBANIS·HAC·INPARTE·MOENIBUS·AMPLIATIS·ET·AD·CHRISTEAM·TURRIM·ANAVISTATIO·PRISCAE·ALTITUDINIS·DUPLO·COLLATIS”75. From a contextual perspective, this phrase can be interpreted simply as: “He raised the walls in this part of the suburb and doubled them from the Tower of Christ until the harbor, when compared to their former height”.

27In 1794, Cosimo Comidas de Carbognano, who was working in Istanbul for the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies became the first researcher to publish the inscription of this slab. Mentioning its Italian form (Torre di Cristo) and without any comments, he simply identified that “Tower of Christ” (Christea Turris) directly as the Tower of Galata. While doing this, he did not elaborate on exactly why this distant slab, located at 500 meters from the tower and on the shore, might be referring to the Galata Tower on the hilltop76.

28Later, British researcher James Dallaway also came across this slab in 1797 and in addition to the architectural identification mentioned above, he misinterpreted the phrase “ANAVISTATIO” (until the harbor) in the relevant part of the inscription as the name of Emperor Anastasios I (r. 491–518). Correspondingly, as the sentence structure changed completely, he also misinterpreted the second part of the quoted Latin phrase as if Maruffo “doubled the Tower of Christ of Anastasios, when compared to its former height” in 1446. Based on his own assumption, Dallaway believed that the Galata Tower had existed since the reign of Anastasios I, therefore he matched this structure with the “Tower of Galata” captured by Geoffroy de Villehardouin during the Fourth Crusade77. However, according to very clear positional as well as functional descriptions of Villehardouin himself and also Khoniates, the aforesaid structure was evidently “Kastellion”, which was located on the coast and where the chain of the Golden Horn was attached78.

29After Dallaway, Patriarch Konstantios I briefly repeated the aforesaid argument without specifying the main source and conveyed it to a wider audience in 1846 that the Galata Tower, which he referred to as the “Tower of Christ” (Tour du Christ) was built by Anastasios I and then raised by the Genoese in 144679. Skarlatos Byzantios, on the other hand, repeated the same argument once more in 1862, and reinforced the misinterpreted statement by falsifying the relevant section as “Christeam turrim Anastasio” (Anastasios’ Tower of Christ) while citing the inscription on the slab80. Supposing that the tower has existed since the time of Anastasios I, he then stated that it was used as a cemetery during the plague epidemic of 541-542 in the reign of Ioustinianos I81. However, Prokopios’ statement that the towers of the walls in Sykai82 were used for this purpose does not refer to a specific tower83. As it has been mentioned before that all the fortifications except “Kastellion” were demolished in 1267, there is no concrete evidence that the Genoese actually took over an older Byzantine tower when they possessed Galata, and that this hypothetical tower was precisely in the same position as the current Galata Tower. In this context, popular claims that the tower was built by Ioustinianos I in 52884 are also unfounded, because this narrative of Ioannes Malalas for 528 is only about the repair of the ruined Sykai walls together with the theater, the construction of a new bridge from Constantinople to here, and the renaming of this neighborhood as “Ioustinianopolis” by declaring it a separate city. It certainly does not refer to any particular tower construction85.

30When it came to 1875, Victor-Marie de Launay, who was commissioned by the municipality during the demolition of the city walls first repeated the argument that the Galata Tower was built by Anastasios I. Besides, while referring to the inscription of the slab in question, not realizing that the claim of Anastasios was actually derived from the phrase “ANAVISTATIO”, he interpreted this part for the second time in a paradoxical and somewhat strange way, and with his interpretation of “άνά VISTATIO” (watching from above), he further strengthened the perception that the “Tower of Christ” in the inscription is the Galata Tower on the hilltop86. Then, Launay stated this time in 1891 that the very same phrase “ANAVISTATIO”—more plausibly—can actually be “A NAVISTATIO” that means “to the harbor”. Yet, in this case, he had difficulty to reinterpret the entire inscription, therefore continued his previous arguments about the slab and the Galata Tower87. Based on an unpublished work of Launay, the marking of the Galata Tower as “Torre del Cristo” (Tower of Christ) in the plan of Belgrano dated 1877 was the first cartographic representation in this context and was frequently repeated on subsequent Galata maps88. Much later, Schneider and Nomidis published the Latin inscription of the slab dated 1446 with an accurate translation in German except the critical word in question, which they identified as “NAVISTATIO”89.

31While the argument after the inscription of the slab that the Galata Tower was the “Tower of Christ” has been continued, it has also been argued that the “Tower of the Holy Cross” mentioned in some testimonies about the Siege of Constantinople could be another name for the Galata Tower90. For example, Mordtmann referred to the Galata Tower only as the “Tower of the Cross” in 1892 and gave the year of its construction as 134891. However, the claims for the “Tower of Christ” continued at the same time92. Yet, all the studies mentioned above did not mention the Tower of the Holy Cross in any way; the tower that was built in 1391 next to the Castle of the Holy Cross on the coast. As a result, a dichotomy appeared for the name of the Galata Tower in the Genoese period, in which the “Tower of Christ” eventually came to the fore and the problem remained unsolved.

A Neglected Testimony : Ciriaco of Ancona

32Ciriaco of Ancona (Ciriaco de’ Pizzicolli, 1391-1452) is a critical contemporary source, who directly witnessed the work of Baldassare Maruffo in Pera at that time, but modern literature overlooked his testimony when discussing the Galata Tower. In a letter he wrote to Baldassare Maruffo sometime after 21 August 1446, Ciriaco states that the walls were raised from the harbor (a Navistatio) to the Tower of Christ and were doubled when compared to their former height. He clearly states that all this work happened in the coastal part93. Moreover, he proposed to place a marble slab on the walls in question as a commemoration of this work that the inscription on the slab placed on the coastal walls on 20 September 1446 was actually composed in this letter directly by Ciriaco and was presented to Maruffo94. In this context, the section “SUBURBANIS·HAC·INPARTE·MOENIBUS” (the walls in this part of the suburb) in the inscription of the slab expresses its physical location in reference to the place of the walls in question, while Ciriaco states in the narrative section of his letter that this place was on the coast. More interestingly, again in the letter of Ciriaco, the original phrase in the section where he proposed the inscription is actually “SUBURBANIS MARITIMA HAC IN PARTE MOENIBUS” (the walls in this coastal part of the suburb).95 However, the word “MARITIMA” that even more clearly indicated the location of the related work was not included for some reason by the stonemason, who carved the inscription of the construction slab in the very end. There is no other primary source that mentions a “Tower of Christ” in Galata.

33As a result of all the problems experienced during the interpretation of the phrase “ANAVISTATIO” in the inscription of the slab dated 20 September 1446, the relevant sentence was misinterpreted. Thus, it was thought that there were two separate works as raising the walls and doubling the height of a tower. Finally, an unquestioned conditioning appeared that the aforesaid tower could only be the Galata Tower. The very critical contemporary testimony of Ciriaco about this work has been neglected, which clearly states the same part by separating it as “a Navistatio” in the narrative section of his letter. As the word “MARITIMA” (coast) in the original inscription proposal of Ciriaco was not written on the slab, the expression was somehow weakened from a positional context. In addition, the problematic phrase that is not found in dictionaries, therefore seemingly caused all this confusion can be considered basically as a compound word as Navi (ship) + Statio (station). When other clues about the inscription are also considered, the rare word Navistatio apparently means “harbor” as suggested by Launay in 1891 and Bodnar today, rather than the strange interpretation of Anastasios I. Therefore, it should be considered that with the expression Navistatio, Ciriaco in fact intended to describe the busy port located in the eastern part of Galata, whose traces can be found in several historical sources96. A fifteenth-century Italian translation of Doukas also uses the same word to mean literally “the port where ships take refuge”97. As a similar phrase, “statio dele naue” often appears in the portolan of Bernardino Rizo da Novara dated 1490, which defines suitable anchorages98. These usages can be shown as examples in order to support the aforesaid analysis for “Navistatio”.

34Finally, the majority of the forty-four Genoese construction slabs with coat of arms and inscriptions that were documented in Galata refer to works that took place in their own positions rather than constructions elsewhere99. As a matter of fact, the first possibility that comes to mind is that the construction slab dated 20 September 1446 is related to the coastline of the eastern suburb as the location of the city walls where the slab was placed, rather than a distant tower on the hilltop. This simple and plausible starting point also coincides with the positional analysis made above for the inscription of the slab, and in fact, with the phrase “Navistatio” (harbor), the slab denoted the coastal area on which it stood.

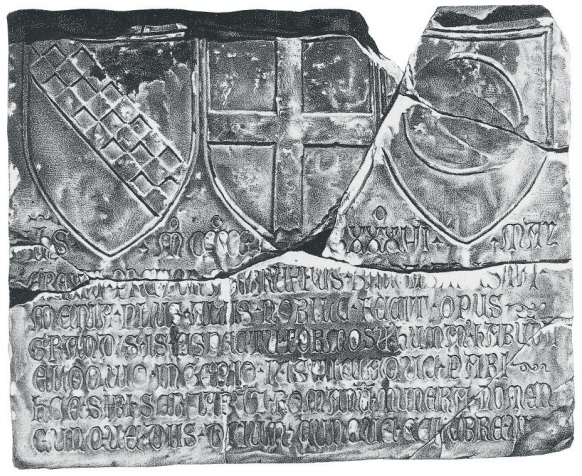

So What Was the “Tower of Christ” and Where Was It ?

35The construction of the coastal walls of the Spiga and Lagirio suburbs of the Pera colony was one of the latest fortifications works carried out until 1453. While the shores of both suburbs appear unfortified in the Biblioteca Marciana copy of the Buondelmonti depiction from circa 1420, in the Düsseldorf copy of the same work from end of the fifteenth century, especially the coastal walls of Lagirio with protruding cannon barrels draw attention100. On this shoreline, according to the inscriptions of two construction slabs that were documented on the Mumhane and Kireç gates, Podestà Filippo De Franchi initiated the coastal walls of the Lagirio suburb in 1430 (fig. 4a) and these first walls were completed in 1431 (fig. 4b)101.

Fig. 4a: Construction slab with inscription dated 1430 that was documented on the coast of the Lagirio suburb (Rossi, Lapidi, 155) (see figure in original format).

Fig. 4b: Construction slab with inscription dated 1431 that was documented on the coast of the Lagirio suburb (Belgrano, Documenti, pl. 10) (see figure in original format).

36Three later slabs reveal that those first walls were significantly improved. An inscription dated May 1446 and documented on the Mumhane Gate states that Podestà Baldassare Maruffo raised these walls and performed “a more distinguished work than the others” (fig. 4c)102. The inscription dated 20 September 1446 and documented on the Eğri Gate further to the northeast was discussed above in detail (fig. 4d). The inscription dated 1447 and documented near the Eğri Gate shows that the improvements on these walls were only completed by the next podestà, Luchino De Fazio (fig. 4e)103. The reason why the first coastal walls completed in 1430-1431 were extensively improved roughly 15 years later, in 1446-1447, is unclear. Perhaps, this may have been needed in response to the increasing Ottoman threat.

Fig. 4c: Construction slab with inscription dated May 1446 that was documented on the coast of the Lagirio suburb (Belgrano, Documenti, pl. 18) (see figure in original format).

Fig. 4d: Construction slab with inscription dated 20 September 1446 that was documented on the coast of the Lagirio suburb (Belgrano, Documenti, pl. 19) (see figure in original format).

Fig. 4e: Construction slab with inscription dated 1447 that was documented on the coast of the Lagirio suburb (Rossi, Lapidi, 156) (see figure in original format).

37Before the demolition of the Galata Walls, the improvements introduced by Maruffo and De Fazio were studied in detail by Louis de Mas Latrie both epigraphically and architecturally. According to his observations, the section dated 1446-1447 from the Mumhane Gate to the Kireç Gate had a much superior workmanship, which was made of large, finely hewn stones. The battlement section for the sentries was carried by a series of brick arches. In the lower sections, embrasures were inserted for cannons and the whole wall course was strengthened through regular rear buttresses. On the other hand, the section dated 1430 from the Kireç Gate to the Tophane Gate was built from a much inferior masonry technique. In this section, there were no series of arches for the upper level but only some stone protrusions, which probably carried a wooden floor to be used as a makeshift crenellation (fig. 5)104.

Fig. 5: Locations of the slabs documented on the coast of the Lagirio suburb and probable extents of the first construction and subsequent improvements along this course. Hasan Sercan Sağlam, 2020 (see figure in original format).

38In this context, the “Tower of Christ” mentioned in the letter of Ciriaco as well as in the inscription of the slab dated 20 September 1446 composed by him should be the tower built in 1391 adjacent to the Castle of the Holy Cross on the southwestern coast of the Lagirio suburb, which was called the “Tower of the Holy Cross” according to the Genoese archival documents. The “Tower of Christ” is seemingly a literary expression to describe that structure, probably because of the cross-bearing orb (globus cruciger) on its top as the sign of Jesus105. The ones whose height had been doubled were the coastal walls between the eastern harbor and this tower. Similarly, the witnesses of the Siege of Constantinople (1453) also used some descriptions for the Galata Tower instead of its name. The literary expression “Tower of Christ” is also consistent when considered the pompous style in the long inscription of Ciriaco, especially when addressing the Pera colony and Baldassare Maruffo.

39Alternatively, it can also be questioned that the phrase “turris” of Ciriaco perchance defined the Castle of the Holy Cross as a whole. While contemporary Latin sources concerning the Fourth Crusade like Geoffroy de Villehardouin106, Ernoul107, Hugues IV de Campdavaine108, Robert de Clari109 and the anonymous Corpus Chronicorum Flandriae110 all defined “Kastellion” (later Castle of the Holy Cross) as “to(u)r” as well as “turris”, only the anonymous Devastatio Constantinopolitana called it “castrum”111. Thus, it was not that uncommon for strangers, perhaps also including Ciriaco, to define this small castle “turris”.

40In any case, it appears that neither the letter of Ciriaco nor the inscription he composed for the slab had anything to do with the Galata Tower on the far hilltop, as they mention very clearly of a work done on the coast. These improvements were started around the tower of the castle and were largely carried out by Maruffo between May and September 1446. They were only completed by De Fazio around the eastern harbor in 1447. Architecturally speaking, all these improvements reached neither the corner tower of 1441 on the far northeast of Lagirio112, nor the Galata Tower further beyond. There was no other tower on the Lagirio coast.

41The expression “Tower of Christ” in the inscription of the slab dated 20 September 1446, which started to be the subject of scientific studies since the end of the eighteenth century probably dazzled the researchers. Since the Tower of the Holy Cross of the Castle of the Holy Cross collapsed in 1766 and then disappeared, if a building with such a glorious name existed in Pera, the scholars unquestioningly conditioned that it could only be the Galata Tower as its major landmark. As the phrase “ANAVISTATIO” (“a Navistatio” in the letter) could not be interpreted correctly, the belief has been strengthened in time. Hence, much more meaning was attributed to the related construction slab than it actually has, which is just one of the forty-four slabs documented in total in Galata. In the meantime, the subject has not been researched in a holistic and detailed way in terms of epigraphy, urban studies and architectural history. This is how the popular claim that the name of the Galata Tower in the Genoese period was the “Tower of Christ” (Christea Turris) emerged. The name “Tower of the Holy Cross” (Turris Sancte Crucis) that will be put forward with this article has not been elaborated enough for both the Castle of the Holy Cross and the Galata Tower.

42Although the Galata Tower is essentially a structure from the Genoese period, many modern sources assumed that its origins date back to the Early Byzantine Period, therefore the history of the monument and thus the Galata district was distorted. Due to a strict conditioning, even the irrelevant testimonies of Prokopios, Malalas and Villehardouin were forcibly associated with the tower. For centuries, the name of the tower in the Genoese period was thought to be the “Tower of Christ” and also the “Great Tower” as discussed below. Moreover, an architectural phase that never actually existed was repeatedly mentioned, as its height was allegedly doubled around 1445/1446. In all this scientific confusion full of inconsistencies, important points regarding the historical and architectural phases of the Genoese period of the tower have been overlooked. The fact that a comprehensive reevaluation has not been made despite such fundamental mistakes can perhaps be explained by the belief in all the wrong assumptions in question due to the well-known reputation of both the tower and the researchers who have commented on it.

Other Misconceptions : The Claims of Murad II and the “Great Tower”

43A Genoese document was attributed to the Galata Tower by Eyice regarding its so-called raising in 1445/1446 and the promise for placing the Murad II’s signature (tuğra) on it in return for supporting that alleged work113. However, that document is actually dated 15 April 1424 and without any “height increase” it clearly mentions a strong and high tower that would be newly built near the weighbridge and marketplace of Pera114. Due to its construction date as 1348 and also hilly position away from all the historical commercial activities along the quays in the Pera colony, the aforesaid document is obviously irrelevant to the Galata Tower. During the Genoese period, many towers with different characteristics were built in Galata.

44Secondly, as previously mentioned, the “megalos pyrgos” (great tower) in the anonymous Greek source that was copied by Zygomalas in the sixteenth century was considered as another proper name for the Galata Tower, from the Byzantine perspective. Yet, it was apparently not a proper name, but a simple, anonymous description based on appearance, like the ones by Clavijo (torre grande), Posculo (summa Galatae de turre) and Isidoros (magnam turrim) in the context of some incidents concerning the Pera colony. Therefore, what name the Galata Tower actually had during the Genoese period needs a much different explanation.

The True Origin of the Galata Tower : Multiple Dedications in Pera

Towers Dedicated to Michael and Mary

45Two construction slabs with coats of arms, bas-reliefs and inscriptions that were documented on the walls, and additionally an archival document indicate that three towers on the Pera fortifications were dedicated to the saints Nicholas (fig. 6a), Bartholomew (fig. 6b) and Christopher115. Similarly, in Ciriaco’s letter dated 1446, it is mentioned that a new tower was added to the upper part of the city walls by Podestà Boruele Grimaldi a year ago, which was dedicated to Archangel Michael116. Moreover, a large bas-relief of Michael was engraved on a slab found on the first tower to the northwest of the Galata Tower and its inscription dated 25 March 1387 commemorates the construction of this tower by Podestà Raffaele Doria (fig. 6c)117.

Fig. 6a: Construction slab dated 1349 with the bas-relief of Nicholas (Belgrano, Documenti, 324) (see figure in original format)

Fig. 6b: Construction slab dated c. 1420s with the bas-relief of Bartholomew (Belgrano, Documenti, pl. 15) (see figure in original format)

Fig. 6c: Construction slab dated 1387 with the bas-relief of Michael (Belgrano, Documenti, pl. 7) (see figure in original format)

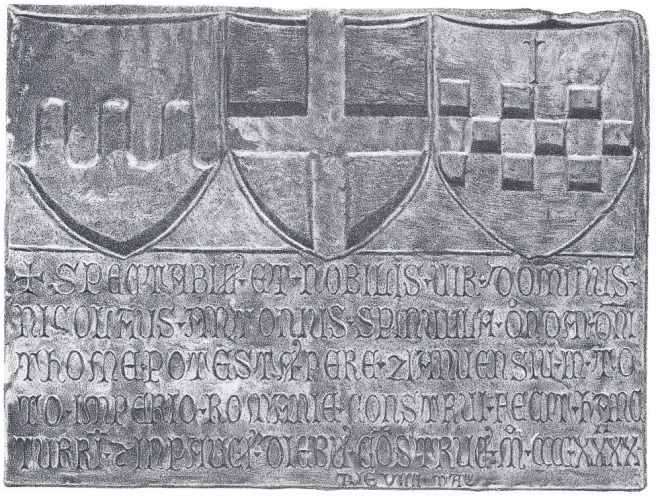

46Another construction slab with inscription documented on the second tower to the northwest of the Galata Tower mentions that this structure was built on 20 October 1442 by Podestà Nicolo Antonio Spinola and was dedicated to Mary (fig. 7a)118. The second marble slab found on this tower has a bas-relief of Mary, surrounded by two saints and holding the baby Jesus in her arms, which is clearly related to the dedication of the tower (fig. 7b)119. An identical slab with the same bas-relief of Mary was also documented on the fourth tower to the northwest of the Galata Tower (fig. 7c)120. On the construction slab of this second tower, apparently attributed to Mary once again, it was inscribed that the tower was built by the same Spinola mentioned above on 9 May 1442 (fig. 7d)121.

Fig. 7a: Construction slab dated 9 May 1442 that was documented on the first tower dedicated to Mary (Belgrano, Documenti, pl. 13) (see figure in original format).

Fig. 7b: Slab with the bas-relief of Mary that was documented on the first tower dedicated to her (Rossi, Lapidi, fig. 7) (see figure in original format).

Fig. 7c: Slab with the bas-relief of Mary that was documented on the second tower dedicated to her (Rossi, Lapidi, fig. 8) (see figure in original format).

Fig. 7d: Construction slab dated 20 October 1442 that was documented on the second tower dedicated to Mary (Belgrano, Documenti, pl. 14) (see figure in original format).

Two Towers Dedicated to the Holy Cross

47From the examples discussed above, it is understood that there were at least four towers in Pera that were dedicated to Michael and Mary in doubles. In other words, multiple towers could have the same dedication. Therefore, the Galata Tower marked as the “Tower of the Holy Cross” in the Düsseldorf version of the Buondelmonti depiction from the end of the fifteenth century and the Tower of the Holy Cross added to the Castle of the Holy Cross in 1391 according to the Genoese archival documents do not cause a contradiction. Moreover, according to the previously cited testimonies of Khalkokondyles, Doukas and Lomellini, the Ottomans damaged the fortifications on the land side, but did not touch the ones next to the coast. A little more detailed statements of Lomellini demonstrate that the damaged Tower of the Holy Cross was on the land side. In addition, the land walls of the suburbs were destroyed and presumably their ruins filled the landward moat, therefore made it useless122. The only building specifically mentioned in Pera by all the primary sources giving information about the Siege of Constantinople is the Tower of the Holy Cross as a defensive landmark with a cross on its top. It is understood that this structure was not on the shore, therefore was obviously the Galata Tower on the hilltop123. Hence, it can be said that in order to avoid a possible confusion, the expense records dated 1391 specifically emphasized that the newly built Tower of the Holy Cross belonged to the castle of the same name.

48The barbican that Lomellini mentioned in his letter must be the semicircular structure surrounding the front of the Galata Tower today, and the curtain walls inside it must be the inner walls extending towards the south of the Galata Tower, which separated the three main suburbs of the colony from each other. According to a construction slab documented on the aforesaid barbican, this addition was completed on 1 April 1452 and became the last fortification built before the conquest of the Pera colony by the Ottomans124.

49In this context, there were three fortifications named after the “Holy Cross” in Pera. The identities of these three defensive structures, being two towers and a castle have not been fully discerned until now. Nevertheless, the researchers who only briefly mentioned the old name of the Galata Tower as the “Tower of the (Holy) Cross” actually made an accurate match, whose place in modern literature clearly fell behind the proponents of the much popular name “Tower of Christ”125.

Defensive Function of the Galata Tower : More Than an Observation Post

50An untrained eye would consider the Galata Tower simply as a symbolic watchtower and would focus on its wide range of vision as how tourists enjoy today. Being lost in the middle of modern urban development, the relationship it once had with the surrounding landscape is barely recognizable in the present day and the exact defensive function of the Galata Tower is usually overlooked. As previously discussed, its midway position on the main ridge with the optimum slope for transportation was the primary landward entrance of the Pera colony, directly on the route of the freshwater conduit. Remaining slopes towards the flanking suburbs with much steeper slopes were logistically disadvantageous in all cases126.

51On the other hand, the main ridge above the colony also posed a threat, as it would be the best route in case of an enemy attack through deploying heavy siege engines from the land side. Confirming this, Ioannes VI Kantakouzenos indicates that the position of the Galata Tower was so steep that it hung above the heads of the colonists along the plain coastline. As it would be the source of much injury for the Pera colony, they wished to occupy this land and surround it with walls, therefore it would not be easy to besiege them. The occupation of this land caused a significant conflict between the Genoese and the Byzantines in 1348-1349127 Being aware of that, Kantakouzenos as the contemporary emperor further states that during the unsuccessful Byzantine siege of Pera from the land side in 1351, led by Manouel Komnenos Raoul Asanes and Georgios Phakrases, the assailants deployed a three-storey wooden siege tower with a suspension bridge in order to exceed the Galata Walls, and with another particular siege engine with a hooked bridge mechanism they intended to set fire one of the flanking towers on the walls, as most of them had wooden superstructures due to material shortages128. In this case, the Galata Tower seemingly became a deterrent on the ridge after its construction around the end of 1348. It appears that the Byzantines, equipped with some inferior close encounter siege machinery omitted facing with the tower by 1351, therefore attacked flanking sections of the colony despite the topographical disadvantage, where regular walls and partially wooden towers were located. When Pera was besieged during the Siege of Constantinople in 1394-1402 by Bayezid I, Ruy González de Clavijo reports that the Ottomans encamped on the hillside before the Galata Tower, launched an attack with torsion artillery from there and threw missiles, though the damage of this failed attempt to Pera is unknown129. The dominant hill in question, mentioned as “Hagios Theodoros” by Georgios Sphrantzes in the context of the siege of 1453 was also the place, where Mehmed II deployed a battery in order to bombard the Golden Horn130. Meanwhile, the tower constituted the focal point of the triangular fortification system of the Pera colony, as Tursun Beg described131. As previously discussed, even though Pera surrendered without a war, one of the first actions of Mehmed II even before concluding the treaty was cutting down the Galata Tower as a safety measure, which further underlines its defensive significance.

52On that strategic position as demonstrated above, the exact defensive function of the Galata Tower was mainly elaborated by Holmes and was linked to a particular period of fortification architecture that was especially promoted by Philippe II Auguste (r. 1190-1223). When more powerful counterweight trebuchet appeared around the end of the 12th century, it surpassed traction trebuchet (mangonel) and earlier fortresses became obsolete. While developments in construction techniques allowed more resistant masonry structures, Philippe II Auguste initiated heavily fortified and regular planned castles with circular corners towers. In the beginning, a large keep (donjon) was positioned in the center of the main courtyard but in later and more advanced examples of this model, that large tower was even moved out of the enclosure and replaced the weakest corner tower. Thus, the passive function of the traditional independently fortified residential or administrative keep and the direct role of a strong combat tower at a vulnerable corner of the enceinte were combined. Firstly, through its ballistically advantageous circular form, the tower resisted advanced torsion artillery as the counterweight trebuchet, and better protected the curtain walls as well as the interior. Secondly, it served as a mounting platform for heavy weaponry to provide counter fire from above. The deployment of men-at-arms and munitions was also eased, which were usually targeted by besiegers. This model was adopted throughout Europe in the following periods, until the dominancy of gunpowder artillery from the second half of the 15th century. An active and forward defense doctrine replaced the former passive, deep defense. In this context, as a large frontline donjon at a vulnerable landward corner, the Galata Tower appears as a descendant of the “système philippienne” that intended to resist heavy siege engines and to secure the rear corner of the Pera colony through a dual function132.

53Finally, it can be argued that the semicircular barbican that was built in front of the Galata Tower in 1452, more than a century after its construction not only provided extra security for the main landward entrance of the colony but also served as a faussebraye against the novel gunpowder artillery on the eve of the Ottoman siege of 1453133. This ultimate addition supposedly intended to secure the vulnerable base of the massive Galata Tower against powerful cannonballs with horizontal trajectory, when compared to the projectile motion of conventional torsion artillery with relatively slower missiles.

Traces of Repairs and the Possibility of a New Architectural Phase

Raising the Tower After the 1509 Earthquake

54Evliya Çelebi states that the 1509 Constantinople earthquake called “Kıyâmet-i Suğrâ” (Little Doomsday) caused great damage on many parts of the Galata fortifications. Subsequent repairs in Galata were commemorated by an inscribed slab prepared by Murad the architect and was placed on the Yağkapanı Gate by the coast. A later repair of the Galata fortifications was carried out by Bayram Pasha, around 1635134. The 1509 earthquake supposedly damaged also the Galata Tower to a large extent that extensive repairs in Constantinople were officially completed in 1510135. As of this period, the tower was named simply after its place136.

55Two successive brick courses on the plain body of the Galata Tower were evaluated as traces of the repairs carried out after the 1509 earthquake, presumably by Murad the architect (fig. 8).

Fig. 8: Brick courses on the second and third floors of the Galata Tower. Photograph: Hasan Sercan Sağlam, 2020 (see figure in original format).

56On one hand, Anadol and Arıoğlu claimed that the part under the first course at the level of the second floor (+13,21 m) remained from the Genoese period137. Eyice, on the other hand, claimed that especially the upper part of the second course at the level of the third floor (+17,17 m) was built by the Ottomans, because the brick motif on this course has a typical Ottoman ornamental character. In this context, according to Eyice, the first course with a plain character should be the level of a superficial repair carried out on the exterior covering of the tower, and the ornamental second course should be the beginning level of the part that is entirely Ottoman construction. Thus, he came to the conclusion that the part under the second or third floors of the Galata Tower is a Genoese construction and the remaining upper part is an Ottoman work138.

57The sections at the top of the plain body walls of the Galata Tower have undergone extensive changes due to several disasters such as fire and storm that happened in 1794, 1831 and 1875. These architectural phases have been documented and presented in detail by using rich visual resources139. The tower gained its present appearance as a result of the extensive restoration work that was carried out between 1964-1967.

Irregularities Between Second and Fourth Floors

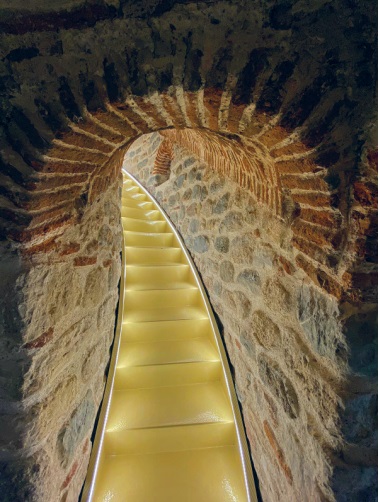

58Galata Tower has eight floors in total, and the first four floors are connected to each other through a brick vaulted gallery with stairs that was placed directly inside the body walls (fig. 9a - fig. 9b - fig. 9c).

Fig. 9a: The brick vaulted gallery with stairs that continues from the ground floor to the fourth floor within the main walls of the Galata Tower. Photo: Hasan Sercan Sağlam, November 2020 (see figure in original format).

Fig. 9b: The brick vaulted gallery with stairs that continues from the ground floor to the fourth floor within the main walls of the Galata Tower. Photo: Hasan Sercan Sağlam, November 2020 (see figure in original format).

Fig. 9c: The brick vaulted gallery with stairs that continues from the ground floor to the fourth floor within the main walls of the Galata Tower. Photo: Hasan Sercan Sağlam, November 2020 (see figure in original format).

59Starting from the fourth floor, the floors are connected through a spiral-shaped wooden staircase that continues through the main interior space of the tower. The body walls, which are 3,75 meters thick until the fourth floor become thinner starting from this floor140. As the aforesaid brick vaulted gallery reduces the thickness of the body walls of the tower, it was positioned mainly towards the south, namely the direction of the safe colony. Thus, the body walls of the tower were positioned with full thickness against a possible enemy threat. The strong body walls of the Galata Tower were intended to resist heavy bombardment due to its protruding position on the frontline, which are much thicker than the average wall thickness of regular towers on the Galata Walls around 1,50-2,00 meters141. In addition, the average dimensions of the bricks used in the vaulted gallery in the interior of the first four floors of the Galata Tower show similarity to the average dimensions of the bricks used in the other fourteenth century fortifications in Galata and in this context also to the Late Byzantine bricks in Istanbul documented in detail by Ersen, Tunay and Kahya142. It is a reasonable possibility that the Genoese of Pera used local materials for the tower at that time.

60The brick courses on the second and third floor levels of the tower were considered by previous researchers as the beginning of the part that was raised again by the Ottomans after the 1509 earthquake. On the other hand, the brick vaulted gallery as well as thicker body walls continue up to the fourth floor (+ 21,09 m) and preserve the same form and material characteristics. The irregular loopholes in the floor plans of the tower and the slight flatness on the southern façade display an uninterrupted continuity from the ground floor to the fourth floor. The fully cylindrical form in plan, the regular loopholes in the floors and the thinner body walls without the gallery only start from the fourth floor (fig. 10).

Fig. 10: Schematic floor plans, section and view of the Galata Tower up to the fourth floor. Hasan Sercan Sağlam, 2020 with corrections and additions after Anadol, Galata Kulesi, 155–156 (see figure in original format).

61Furthermore, the first brick course on the second-floor level (+ 13,21 m) marks an important change on the exterior masonry. The section below this brick course has roughly hewn, large, and mixed type of stones and brick fragments between them. Dark yellow, light brown, dark gray and dark blue stones are distinctive. Stones are roughly square and the courses they form are irregular. On the section above the aforesaid brick course, there are no brick pieces between the stones, which are smaller than the ones below, rather well shaped and have horizontal rectangular shapes. The stone courses are relatively regular and horizontally better arranged. Limestone is the most common type and yellow and brown colored stones are almost completely absent, while dark gray and bluish ones are still present ().

Fig. 11: The masonry technique that changes with the brick course on the second floor of the Galata Tower. Photo: Hasan Sercan Sağlam, 2020 (see figure in original format).

62In this case, it is possible to argue that neither the first brick course on the second-floor level (+ 13,21 m) nor the second brick course on the third floor level (+ 17,17 m) alone represent the level that separates the Genoese and Ottoman works. The collapse line resulting from the 1509 earthquake should have been much more irregular than straight as previous researchers had assumed, and apparently had a higher level in the interior. The thicker body walls starting from the entrance level and continue until the fourth floor (+21,09) together with the brick vaulted gallery support this hypothesis that the end of the vaulted gallery has an even higher elevation (+ 23,00 m). On the other hand, the obvious change of the exterior masonry technique after the first brick course indicates that the exterior damage and material losses caused by the earthquake extended all the way to the second floor. Thus, during the Ottoman period, the thicker body walls and the vaulted gallery were largely preserved in the interior until the fourth floor of the tower, and gradual repairs should have been carried out between the second and fourth floors on the exterior. Finally, on the fourth floor, the entire section was leveled, and a new work with thinner body walls and a different staircase system was carried out. It is possible to say that the brick courses on the second and third floors of the tower serve as beams for a balanced weight transfer between the repaired parts and original walls143.

63As a basic presumption, when considered the remained section of roughly 23 meters and the shortening of 7,5 meters quoted by Ahmed Vefik Pasha, it can be said that the original Genoese tower was at least 30 meters high, which is far less than the tower today. Yet, the exact height of the tower during the Genoese period is still absolutely unknown and nothing certain can be said, as it cannot be determined with the available data144. Furthermore, the common loopholes on the supposed Genoese section of the Galata Tower seem unsuitable for archers due to their deep and narrow form and also uncomfortably inclined bases. They probably only served in order to provide air and light to the interior except for the three large loopholes on the third floor that were probably proper embrasures, while the main firepower of the tower was presumably provided from the wide platform on its battlement level.

The Phase Indicated by the Brick Course on the Third Floor and the Related Testimonies

64As there is an architectural continuity from the ground level up to the second floor on the exterior and to the fourth floor in the interior, this part can be dated to the Genoese period. However, it does not seem possible to attribute the section just above as a whole to the repairs after the 1509 earthquake. In fact, the second brick course on the third-floor level (+ 17,17 m) has an Ottoman ornamental pattern only on its one quarter towards the south, just like the whole brick course that separates the sixth and seventh floors on the top of the tower. The remaining three quarters have a plain character, like the whole first brick course of the second-floor level (+ 13,21 m). This specific aspect was overlooked by Eyice145. In addition, there are long diagonal cracks at the junctions of those different parts of the second brick course (figs. 12a–12b).

Fig. 12a: The SW point where the pattern of the brick course on the third floor of the Galata Tower differs, and also the diagonal crack on it. Photo: Hasan Sercan Sağlam, 2020 (see figure in original format).

Fig. 12b: The SE point where the pattern of the brick course on the third floor of the Galata Tower differs, and also the diagonal crack on it. Photo: Hasan Sercan Sağlam, 2020 (see figure in original format).

65Thus, the second brick course, which is located above the exterior masonry that differentiates with the first brick course below, also differentiates within itself and points to another, later architectural phase. In this case, on the exterior of the Galata Tower and above the part assumed to be from the Genoese period, there are actually at least two architectural phases rather than one. This situation has never been mentioned before.

66Other than the earthquake of 1509, the only known event that caused significant damage on the main structural system of the Galata Tower was the destruction of 1453 that was mentioned by certain primary sources. All the damages and repairs in the following centuries affected much higher parts of the building. It was mentioned that the Galata Tower was partially shortened in 1453 and was raised again by Zağanos Pasha shortly afterwards.146 In addition to this, Evliya Çelebi states by the seventeenth century that the Galata Tower, which he called the “Başhisar” (Donjon) was a construction of Mehmed II with a great height of 118 arşın147. The mention of the Galata Tower as “Kulle-i Cedide” (New Tower) in the late 15th century endowment charter of Mehmed II is another important detail in this regard. The tower also gave its name to the neighborhood, where it was located at that time (Kulle-i Cedide Mahallesi). There was a wall that surrounded its front, which must be the semicircular barbican148. In this context, perhaps the most important visual source for the 1453-1509 period, where the tower probably had a different appearance than its Genoese period is the Düsseldorf copy of the Buondelmonti depiction dated circa 1485-1490. There are significant architectural differences between the depictions of the Galata Tower in the Biblioteca Marciana from circa 1420 and the Düsseldorf copy (fig. 13-fig. 14)149.

Fig. 13: The depiction of Constantinople by Buondelmonti (Buondelmonti, Liber insularum archipelagi, c. 1420). Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Ms. Lat. XIV.45 (=4595) (see figure in original format).

Fig. 14: The depiction of Constantinople by Buondelmonti (Buondelmonti, Liber insularum archipelagi, 1485–1490). Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Düsseldorf, Ms. G 13, fol. 54r (see figure in original format).

67For example, while the roof of the tower was a narrow and high cone surrounded by a series of battlements in the former copy, this roof is much lower and wider in the latter copy and the eaves protrude from the battlements. Moreover, the depiction in the Düsseldorf copy has a single course dividing the main body of the tower in half as if a repair trace, therefore bringing the destruction and repair of 1453 to mind, but this interpretation is only a superficial assumption for now.

68Under these circumstances, based on only the limited data available, it is still early to clearly demonstrate a new post-Genoese architectural stratification directly on the tower’s present structure, especially concerning the period of 1453-1509. This subject actually goes beyond the period covered by the article. However, the curious situation indicated by the irregular brick course on the third floor of the tower still stands out as another architectural issue that awaits further clarification.

Conclusion

69Documented on the walls once existed in the coastal area stretching from Galata to Tophane in the east, the Latin inscription of a Genoese construction slab dated 20 September 1446 alone has led to the emergence of three fundamental arguments about the Galata Tower, which are widely known today and have become anonymous over time: A first construction by Anastasios I, the “Tower of Christ” (Christea Turris) as its name during the Genoese period, and later doubling in height. It can be said that the conditioning that the “Tower of Christ” mentioned in the inscription could only be the Galata Tower caused the emergence of those arguments. The usage of a rare word (Navistatio) in the inscription that needs further etymological research caused the text to be perceived very differently by the researchers, who failed to interpret that word correctly. However, when the more obvious meaning of the word as “harbor” in the light of all the available data, the letter with an inscription proposal written by Ciriaco of Ancona as a contemporary witness, and the other relevant construction slabs placed on the Galata Walls are considered together, the work mentioned in the inscription has nothing to do with the Galata Tower. The work in question was about raising the coastal walls extending to Tophane, which were built in two phases between 1430-1431 and 1446-1447. An architectural analysis made by Louis de Mas Latrie in the mid-nineteenth century before the demolition of walls also supports this conclusion. There is no concrete basis for matching the phrase “Tower of Christ” that was used in the context of some Genoese defensive improvements on the coast, with the Galata Tower on the far hilltop.

70The “Tower of Christ” mentioned in the letter of Ciriaco and in the inscription composed by him was the Tower of the Holy Cross, which was built in 1391 next to the Castle of the Holy Cross Castle (today Yeraltı / Kurşunlu Mahzen Mosque) on the Galata side of the same coastline. Detailed information about this tower can be found in the Genoese archival documents. The reason why this tower was depicted as the “Tower of Christ” by Ciriaco must have been the cross-bearing orb as the sign of Jesus on top of the related tower. There is no other primary source that mentions the “Tower of Christ”. By the end of the eighteenth century, when the inscription in question first began to attract scholarly attention, the Tower of the Holy Cross as the second most important tower of Galata had long since disappeared due to an earthquake. This situation seemingly caused the tower in the inscription to be mistaken for the Galata Tower.

71As can be seen from the testimonies of the Siege of Constantinople (1453) and the Düsseldorf copy of the Buondelmonti depiction dated circa 1485-1490, the name of the Galata Tower in the Genoese period was the “Tower of the Holy Cross” (Turris Sancte Crucis). In fact, this claim was defended by only a few researchers and remained in the background in the face of the rooted “Tower of Christ” argument that emerged earlier. Construction slabs and archival documents confirm that there were other multiple dedications in the fortifications of the Pera colony. In this context, there were at least four towers that were dedicated to Michael and Mary in doubles. There were three fortifications called the “Holy Cross” in total, one of which was a castle and two of which were towers, and there was a large cross (highly likely another cross-bearing orb) on top of the Galata Tower. The primary sources that mentioned the Galata Tower anonymously preferred the description “large tower” in their own languages.