- Accueil

- > Livraisons

- > Cinquième livraison

- > De epigraphia pictorica. The case of Valencia (13th-16th century).

De epigraphia pictorica. The case of Valencia (13th-16th century).

Par Julio Macián Ferrandis

Publication en ligne le 27 septembre 2023

Résumé

This article is a summary of my doctoral thesis (Universitat de València, 2022), focused on the study and edition of the inscriptions present in Gothic and Renaissance painting in the kingdom of Valencia, between 1238 and 1579. Thus, in the first part I study all the compositional elements of these epigraphs —figurative supports, type of writing, origins of texts, language of writing, etc.—, while in the second part I relate these inscriptions to the society of the time, trying to find out who design them, for what purpose illegible epigraphs were included in the paintings or to whom they were addressed.

Cet article est un résumé de ma thèse de doctorat (Universitat de València, 2022), centrée sur l'étude et l'édition des inscriptions présentes dans la peinture gothique et Renaissance du royaume de Valence entre 1238 et 1579. Ainsi, dans une première partie, j'étudie tous les éléments de composition de ces épigraphes —supports figuratifs, type d'écriture, origine des textes, langue d'écriture, etc.—, tandis que, dans une seconde partie, je mets en relation ces inscriptions avec la société de l'époque, en essayant de savoir qui les conçoivent, dans quel objectif les épigraphes illisibles ont été incluses dans les peintures ou à qui elles étaient adressées.

Mots-Clés

Table des matières

Texte intégral

I. Introduction

1Seeing a medieval altarpiece is always a surprising experience. Its dimensions, the brilliance of the gold or the many details that populate it make us look at the «dark» Middle Ages with different eyes. However, one aspect of these works that goes unnoticed by most viewers is the prolific epigraphic programme that the altarpieces usually have. From small INRIs to long biblical quotations, passing through Patristic texts, fragments of literary works or winks to the persevering reader.

2Unfortunately, as I say, these texts not only go unnoticed by the public —understandably so, given that they are usually written in complex Gothic characters and in Latin— but they are also overlooked by scholars. Art historians, perhaps those who should be most interested in these epigraphs, consider them to be a simple complement to the image, something secondary in the composition, which does not contribute anything different to what the figures already express. For their part, scholars of written cultures, both palaeographers and epigraphers, also tend to regard inscriptions in painting as a second-rate graphic element, much less interesting than manuscripts, documents or epigraphs on stone. Fortunately, in recent years there has been a revaluation of these elements1, above all thanks to the interest in all graphic manifestations promoted by Professor Armando Petrucci2, encompassed under the term «History of Written Culture»3 and the titanic work of the Poitiers research group led by Professor Robert Favreau4 and his disciples. However, their methodology, already consolidated in their respective countries and elsewhere in Europe, is still in its infancy in Spain, where we only find a small work by Professor Francisco M. Gimeno Blay—Professor of Paleography and Diplomatic at the University of Valencia and disciple of Armando Petrucci— on the Catalan epigraphs of late medieval painting5, and some other work6 that has emerged more or less in parallel to the research I am presenting here.

3So, when Professor Gimeno Blay proposed that I work with him on a doctoral thesis in which I would compile and study inscriptions in Gothic and Renaissance painting and combine the study of writing, art and society, I accepted the challenge, still unaware that I would be facing a historiographical vacuum. This obliged me at first to delimit very clearly the object of study, the objectives to be met and the methodology to be followed. Over the years, my research converged with the work of Professor Vincent Debiais, thanks to which it evolved from a purely descriptive study to one that sought to understand the inscriptions on medieval and early modern paintings in a comprehensive manner, both in terms of the physical and internal aspects of the inscription and the use given by the society that created it7.

II. Prolegomena

4Due to the universality of these epigraphic practices, it has been necessary to delimit the field of study geographically and temporally. In this case, we have chosen the kingdom of Valencia —a state integrated into the Crown of Aragon— between the 13th and 16th centuries, as it was one of the richest and most pictorially active peninsular territories of this period.

5In order to achieve the main objective, it is necessary to split it into different secondary objectives: to create a catalogue that includes all the inscriptions of Valencian painting from this period, analysing their external and internal characteristics —the figurative supports on which they are inscribed, the scripts used or their sources— and to understand their social function, that is, to relate them to the society of their time and the functions it gave to these writing objects, trying to answer the questions of who commissioned these epigraphs, what inspired them, how they were designed and what they were used for.

6In this sense, the preparation of the catalogue of inscriptions has been fundamental for this study: never before had a catalogue been made of all the epigraphs of Valencian painting —in the same way that there is no corpus that includes such a large number of works in the artistic historiography of this territory— and it is also important as it constitutes the basis on which the subsequent study of the written messages, their characteristics and their social functionality has been built.

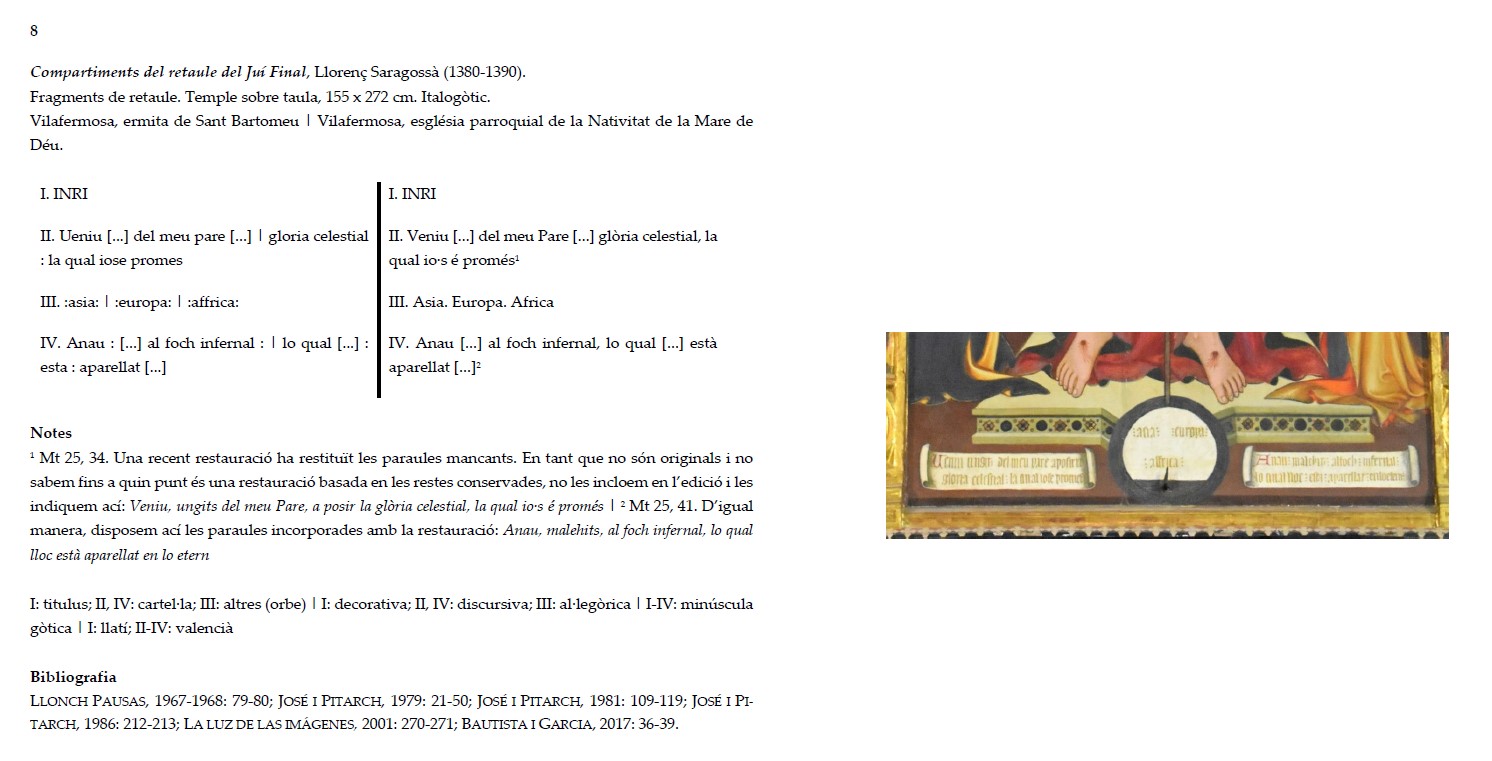

7Thus, each of the 368 entries in the catalogue contains the basic technical details of each work —name, author, chronology, technique and dimensions, place of origin, place of conservation, style, etc.—, the transcription and critical edition of each inscription on the painting, the characteristics of the epigraph —location in the painting, type of inscription, type of writing, language— and, lastly, a bibliographical section listing the main reference works on the painting in question. In addition, whenever possible, it is accompanied by a general or detailed image of the altarpiece (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Example of an entry from the catalogue of epigraphs

III. Pars prima: a description of the epigraphs and their components

8The systematisation of the components of the inscriptions, both the physical features —supports, writing— and the intangible ones —sources, languages, internal functions— allows us to gain an in-depth knowledge of the inscriptions under study, which has been made possible thanks to the catalogue of inscribed paintings.

9Starting with figurative supports, these play a fundamental role in delimiting texts in space and conditioning their perception depending on their morphology8. Phylacteries, closely related to orality, are the most common medium9. They generally include texts that identify the characters or scenes, although they also establish dialogues between the figures or between the figures and the spectators10. The written messages also find in books one of the most common supports. As books are, by definition, containers for writing and, at the same time, objects of veneration, they are represented in two different ways: on the one hand, realistically: they offer the viewer a text, as the normal function of a book. In this sense, we find characters reading books where we can also identify the text, even if this is not its ultimate «purpose». On the other hand, we find the opposite case, in which the content of the book is shown directly to the audience, to whom it is addressed. Inscriptions of this type tend to have a marked allegorical character11. Apart from these, other types of supports are also used, which have a lesser representation, such as cartouches, vestments or haloes (fig. 2). A special case is that of the titulus crucis, very abundant for obvious reasons, but whose content —the INRI— was perceived more as an icon than as its true nature, an abbreviated text.

Fig. 2. Inscriptions on different supports. Valencia, Museu de Belles Arts. Annunciation, Jacomart, ca. 1400. Detail.

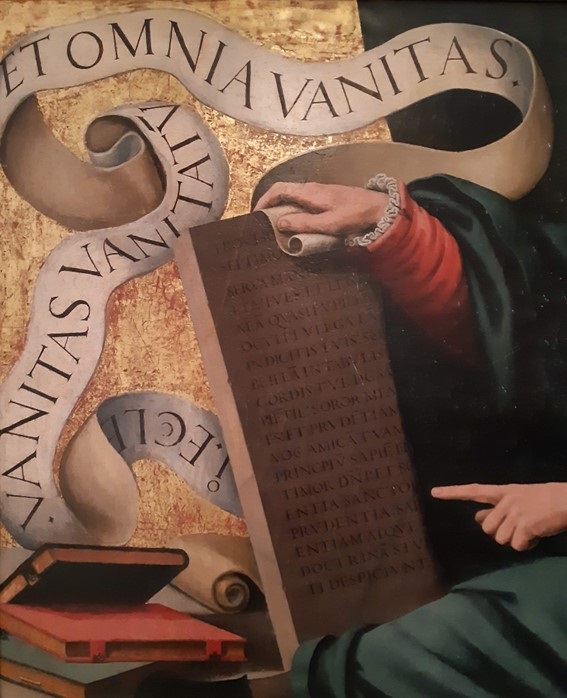

10The chronology covered by this study, mainly the late Middle Ages, means that there is an absolute prevalence of Gothic scripts. The paintings are a privileged testimony to the conquest of graphic space by lower-case letters to the detriment of capital letters12. They also offer a clear view of the evolution of lower-case letters from the more rounded forms of the 14th century to the fractured and calligraphic forms of the 15th century13 (fig. 3), as well as the situation of relative multigraphism that prevailed during the second half of this century and the first decades of the following century, with the introduction of new scripts and their coexistence with the previous graphic types. Among these new scriptures, the prehumanistic one stands out, with a long history in the Valencian pictorial-epigraphic sphere, from the 1440s to the 1520s14 (fig. 4). Likewise, the classical capitals had a timid start, being cultivated only by the Italian Paolo da San Leocadio during the last quarter of the 15th century, although they experienced a growing use from 1500 onwards, which ended in their definitive triumph in the 1530s thanks to the Macip family. Joanes, the most prominent representative of this family, used elegant Roman capitals that put an end to the situation of multigraphism in this field of study15 (fig. 5).

Fig. 3. Rounded Gothic «Com escreví sent Lluch lo sant evangeli davant la Verge Maria. In illo tempore missus est». Valencia, Museu de Belles Arts. Scene of the life of Saint Luke, Llorenç Saragossà, 1370-1375. Detail. Benito Doménech-Gómez Frechina, 2005: 24-29.

Fig. 4. Prehumanistic. Xàtiva, Saint Felix Church. Main Altarpiece, Master of Xàtiva et al., 1494-1505. Detail. Company Climent, 2005: 117-132.

Fig. 5. Roman Capital. Segorbe, Museo Catedralicio. Salomon, Joanes, ca. 1545. Detail.

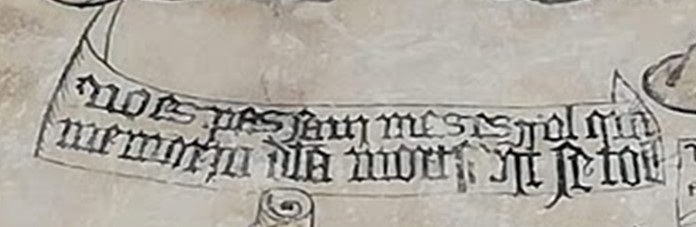

11Turning now to the sources of the texts, it is not surprising that, given the nature of the paintings, most are of biblical origin. Some texts are taken directly from the Holy Scriptures and appear in the scenes as part of the narrative of those events, such as the Angelic Salutation in an Annunciation. In other cases, the texts, although taken from the Bible, acquire a new meaning through their use in the liturgy, connecting the Holy Scriptures with painting, the divine offices and the parishioners. For example, the Gloria in excelsis Deo (Lc 2, 14) is not only part of the Gospel narrative of the Birth of Christ but is also an antiphon of various offices of the Natalis Domini. Some texts, on the other hand, are written ex professo, either as a simple explanation of the scene or with a deeper meaning, such as the inscriptions relating to the brevity of life in the Dance of Death in the Franciscan convent of Morella (fig. 6).

Fig. 6. «No és pas savi, més és foll, qui memòria de la mort sovint se toll». Morella, Convent of Saint Francis. The Dance of Death, anonymous, 1400-1433. Detail.

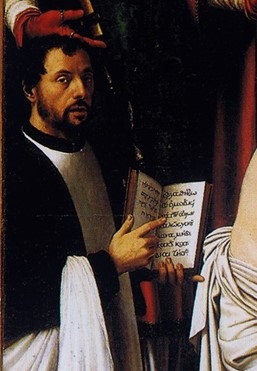

12If the sources are eminently sacred, the prevailing language cannot be other than Latin. However, Valencian —the vernacular variant of Catalan— is dominant in some areas: proper names, didascalia and those related to death16. More interesting are the few examples of the use of other languages. Thus, Castilian appears in works from the interior of the territory —Castilian speakers— or by painters from the neighbouring kingdom. The presence of Arabic is quite significant, although «unintentional», as it appears insofar as the painters copied the inscriptions from the Islamic textiles used as models in their workshop, unaware of the meaning of the writings17. Finally, some examples of Hebrew and Greek can be related to painters who were converts, such as Bartolomé Bermejo, or to humanist patrons, such as Joan Baptista Anyés (fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Book with an inscription in Hebrew and Greek. Valencia, Cathedral. Baptism of Christ, Joanes, ca. 1535. Detail. Benito Doménech-Galdón, 1997: 132-135.

IV. Pars secunda: epigraphs and society

13Having analysed the compositional aspects of these epigraphs, we now consider what their functions were, not within the painting, but in relation to the cult and the community that made use of them. As has been seen, a large majority of these texts lack the doctrinal depth to justify the hackneyed topos of the Bible in pictures, or at least a graphic complement to the image. The inscriptions studied are, on the other hand, repetitive and simple, without contributing anything different to what the image already does. In addition, they are located at a great distance from the viewer —as the altarpieces are in chapels, spaces closed to the public— or are imperceptible to the eye —due to their position at the top of the painting, their semi-hidden position on vestments and haloes or their morphology—. So, we wondered which was the point of including texts in the paintings that, in the end, are not going to be seen or read (fig. 8).

Fig. 8. «Invisible» inscriptions marked in this altarpiece. Catí, Church of the Assumption. Altarpiece of Saint Lawrence and Saint Peter Martyr, Jacomart and Joan Reixach, ca. 1460.

14In this sense, the contributions of professor Debiais are very interesting. In his research, he applies a set of concepts to understand the relationship between the inscriptions and the work of art in which they are located, following the Petruccian precepts of the History of Written Culture. The first of these is that of the «iconocity of writing»18, id est, the iconic value of any text. Its importance lies in the fact that, thanks to its application, it is possible to understand that the verbal message transmitted by an inscription is not the only one, but it also contains an iconic message. In this way, anyone looking at an inscription, regardless of their level of literacy, could perceive the symbolic message inherent in a writing or associate it with an idea, such as the Roman capitals with the classical world or its humanist present. Moreover, the constant repetition of formulas, such as the INRI or the Ave, gratia plena, allows people accustomed to their presence to see them not as a graphic whole but as an image, and to apprehend their content without the need for an effective and complete reading.

15Another concept is that of «agency», the capacity of a given element to act on its environment19. Thus, the texts in the painting are not —at least not solely— designed to offer a specific message to an audience but fulfil an internal function. They are therefore a tool in the hands of the designer or painter, since by giving entity to the object they accompany, they allow or activate its existence. Taking the Annunciation as an example, the phylactery with the Angelic Salutation is not only the arrangement of some words of the Holy Scriptures in a Gospel scene, but also allows that this representation is indeed the announcement of the archangel Gabriel to the Virgin and not any other angelic apparition to a woman, such as those of Saint Anne or Saint Elizabeth.

16Both concepts modify our perception of the inscriptions. If, according to the iconicity of writing, the actual reading of an inscription is not necessary to transmit a message; and if, according to the agency, many inscriptions have an active function within the painting, it is appropriate to change the focus of the public's attention and fix it on the inscription itself. Thus, the inscriptions do not have a publicity intention, this is, they are not intended to convey a verbal message. Rather, they manifest an epigraphic intention, which is why they seek the material concreteness of a specific text in a specific place20. The importance of this approach for our study is indisputable, as it leads to the resolution of questions such as the illegibility of many of the captions, their function in the painting and their relationship with the possible recipients.

17All this makes it necessary to establish a series of changes in the analysis of the inscriptions on the painting. Firstly, if the function of an inscription is to be in a specific space, visibility and legibility are secondary aspects, which is demonstrated by the large number of illegible inscriptions21. This fact leads to the second change. If the inscriptions are neither read nor seen, to whom are they addressed? A distinction should be made between the audience and the addressee of the message22. The two can be coinciding, like an epitaph in a private chapel; non-coinciding, like a prayer inscribed on the halo of a saint, who will be the addressee, while the audience will be anyone standing in front of the altarpiece; or having an addressee but not an audience, as in the case of inscriptions placed in inaccessible places, such as stained-glass windows.

18Ultimately, it has been concluded that many inscriptions were not intended to be read, or even seen, and are therefore not addressed to a specific audience. In this case, the point of view of epigraphic communication needs to be changed. On the one hand, the publicity of a message, this is, its dissemination, is not a priority; what is important is the presence of the text and its possible reading is a secondary effect of its physical materialisation. On the other hand, the communicative process is not linear: the author does not elaborate a message to get it to a specific audience. Rather, it is a multidirectional communication: the author intends to convey an idea using epigraphic writing. This has a strong symbolic value per se, which allows it to act as an image. Thus, the inscription can be perceived iconically or graphically by the public, it can act on the images it accompanies and it can be a simple tool in the hands of the designer used during the creative process of the work.

19Another very important aspect is the distinction between those epigraphs that are traditionally associated with a character or scene and those that are introduced ex novo into the pictorial programmes. These are what Pozzi calls citazioni reliquie and citazioni culturali23. Traditional inscriptions should be treated from the perspective of iconicity since the public would be familiar with their presence and would not need to read them in order to know the content of the texts. As for the culturali, their ability to act on the image and the pictorial whole is preponderant. The introduction of an unusual or purposely elaborated text is never accidental and denotes certain intentions of its author. A narrative inscription is not only conceived so that the public that reads it knows the facts represented, but its presence allows its existence, which makes it take on its full meaning.

20Like manuscripts and other graphic products, the work of art must be understood as an object with a specific social and cultural function, produced to satisfy the needs of a particular group. It is therefore necessary to know the people involved in the process of making the painting and, consequently, its epigraphic programme, as well as the purpose of the piece.

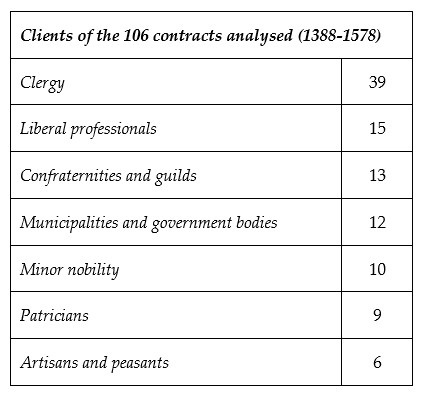

21An analysis of Valencian painting contracts leads to some very interesting conclusions regarding the composition of the artistic clientele24. The most active group is the clergy, but slightly less than half are involved in a private business, commissioning works for their own chapels. The rest of them contracted paintings as heads of their respective churches. In both cases, the canons of Valencia cathedral stand out. The next category is that of liberal professionals, the most active being those related to law. They are closely followed by guilds, trade associations, municipalities and other government bodies. Next, we find the members of the lower nobility, especially widow women, who participated as executors of wills. The number of patricians is similar. Finally, with a rather reduced participation, there are the artisans and farmers, although they usually act in the art market through the confraternities and corporations. From this information what unites almost all the social categories involved is their close link with written culture. For this reason, they would have the capacity and the necessary materials at their disposal to be able to design the epigraphic programme of their commissions (fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

22As for the cultural intermediaries, they are a mysterious figure of whom little documentary trace has survived25. On the basis of the information available, we can say that they were ecclesiastics who could put painters in contact with clients; others were responsible for the intellectual design of the work, telling the painter which scenes were to be depicted and the most appropriate way of doing so, as can be seen from the documents, which state, for example, that the iconographic programme of an altarpiece was «ordinatum per reuerendum et religiossum fratrem Anthonium de Canalibus, magistrum in Sacra Pagina Ordinis Predicatorum»26; and others, with artistic skills, would even design the basic outlines of the new altarpiece, giving the painter a sketch or outline of what he was to execute. Andreu Garcia, priest with an ecclesiastical benefit in the Valencia cathedral, stands out among the best-known cases. This personage, who was related to the patricians and aristocracy of the kingdom, had a close relationship with artists such as Joan Reixach, Gonçal Peris Sarrià and the illuminator Pere Bonora, to whom he left models and drawings in his will27. Likewise, Garcia appears in documents as the intellectual author of some of the paintings, indicating the subjects to be represented. He even designed two candelabra in the shape of angels28, which leads us to believe that he may also have been actively involved in the production of paintings.

23As for the painters, some researchers claim that their involvement in the design of the works would be minimal, citing their illiteracy29. However, even if the literacy rates among the painters were low, it is obvious that they would have had a well-established knowledge of Christian iconography30. We must not forget the existence of drawing albums and the circulation of models in medieval workshops31, as an eminently visual craft could not do without these materials, as can be seen in the post-mortem inventories, where we can find mentions of «molts papers ab imatges deboxades del ofici del dit defunt»32. We know of literate painters such as Joan Reixach, Nicolau Falcó and Vicent Macip, just those who were responsible for most of the conserved contracts. Thus, they could count on flores sanctorum and other devotional books to help them in the design of their works, without the need to resort to religious figures. An exceptional case is that of Joanes, who had a profound humanistic training and contacts with the city's intelligentsia33.

24Although the Valencian archives are rich in medieval and modern artistic documentation, the contracts provide little information about the inscriptions. As a testimony of a commercial transaction, they contain important information in this sense, such as the subject of the piece, the materials or the price. However, a careful reading of the documents provides some insight into the process of execution of the work, which can be extrapolated to the subject34. There are mentions of pre-existing paintings by the client, such as the executors of Pere Ros, who asked for a new altarpiece that, following the last wishes of the deceased, would have a «crucifixi semblant que és en lo dit retaule de sent Agostí» of Morella35. If the client wanted his altarpiece to be the same as another, there is nothing to prevent us from believing that the inscriptions on the model could also be included. Furthermore, later conversations between clients and painters are mentioned in which the figures to be included or the subjects to be depicted were specified in detail. This can be seen in the contract for the main altarpiece of the collegiate church of Gandia, which states that Paolo da San Leocadio was to paint « les ymatges dels sancts que la dita il·lustre senyora duquesa volrà e elegirà »36. In this way, the client could detail all the elements he wished to incorporate into his work, including the inscriptions. There are some references to epigraphs in certain contracts. Far from being concrete specifications, in these cases they are reflected because the client speaks of their materiality, as for example the canon of Valencia Francesc Dàries, who wants his altarpiece to have an «Iesus Christus» in gold letters37. Apart from a few mentions such as this nomen sacrum or «les letres del títol de la Creu»38, there is only one specific case where the client details the inscriptions to be included in his painting. The contract between Lluís Caldes and the painter Pere Cabanes states that «als peus de la Verge Maria sia hun àngel ab hun títol que diga: “Assumpta est Maria in celum”»39. This is an exceptional case, undoubtedly due to the detailed personality of the commissioner. The contracts also mention mostres, sketches in which the painter presented the final appearance of the piece to the client40. The few surviving examples are drawings of the structure of the altarpiece, with some annotation of the themes of each panel. A similar case is that of sketchbooks and letter samplers. Few have survived, and those that have survived do not usually contain examples of figures or scenes with the most common inscriptions. For example, the Uffizi notebook, which is thought to be Valencian41, contains various scenes —such as an Annunciation— with empty phylacteries. However, sketchbooks by painters have survived that did include artistic representations of certain alphabets, such as the anthropomorphic Gothic letters of the taccuino of the Trecento painter Giovannino dei Grassi, in which we also find inscribed phylacteries42. There is therefore nothing to prevent us from believing that the painters would have had many of these books containing the most common texts, but that, after their death, they would have been sold at public auction or passed from hand to hand until they were destroyed by the passage of time or were no longer in keeping with the prevailing fashion. In the same way, the painters could have models of letters, such as those mentioned in the inventory of Andreu Garcia's assets and which, perhaps, are the ones he left as an inheritance to his friends Reixach, Sarrià and Bonora: «qüerns scrits en paper en forma de full [...] on se mostren formes de letres» or a book «appellat Formulari de letres»43. These graphic exempla would be offered to their clients, as manuscript copyists did, so that they could choose the models they liked best, or which best suited their order. At the end of the 15th century and especially in the 16th century, treatises on calligraphy —such as the Regola a fare letre antiche44— explained the geometrical construction of classical letters, which seem to have been very popular with painters, sculptors and architects.

25The stages in the execution of the inscriptions are like those of painting45. The nature of these written messages, however, makes it necessary to follow the nomenclatures established by epigraphy. The first phase would be the delivery of the minutes with the basic information of the text, the step prior to its design. For our epigraphs, this would not always be necessary. Many of them belonged to the tradition, so it would not be necessary to make their inclusion explicit, such as the Gloria in excelsis Deo in the Nativity. As for the citazioni culturali, as they are not texts supported by custom, the client would be obliged to give the painter a minute with the full message. Once the painter had the epigraphic programme, the ordinatio phase began, this is, the preparation and design of the inscriptions. The impaginatio, an internal stage, which in classical epigraphy is attributed to a professional who designed the inscription, would have been carried out by the painter himself, as it is not credible that in artistic workshops someone would have been hired only for a task considered secondary to his daily activity. It is interesting when it was necessary to make decisions on the aspect of the inscription, such as the graphic type, because it shows the relationship of the clients with the written culture. Due to the concept of the iconicity of writing, the choice of a graphic type is not trivial, because each one transmits an idea or an impression to the receiver. When someone looks at a text in Gothic minuscule, for example, they would directly link it to scholastic culture. In any case, a real choice would only be made at those moments of change or graphic transformation, at the end of one writing and the beginning of another. If a graphic type was in use, it was only necessary to select the pole of attraction. The graphic models used would be handwritten books, letter samplers and calligraphy treatises, depending on who designed the inscriptions. Thus, if the commissioner was the client himself, he could use models from books of his personal library or of his place of work. If, on the other hand, was the painter who design the inscriptions, it would be easier to believe that he would use models of letters from his workshop.

26With the choice of the graphic type, the final phase of the ordinatio would be reached and would be followed by the translitteratio —the transfer of the design on paper to the final support— and the incisio, the last stage, which in our case must be understood as the application of the final layers of paint, with which the inscription would be completed. This would finalize the process of gestation and execution of the epigraphic programme, simultaneous with the creation of the rest of the altarpiece.

27What remains to be analysed is the aspect that gives meaning to all the above and which constitutes the core of this study: the display and use of the painting's epigraphs46. The purpose of an altarpiece is to fulfil its role as a setting for the liturgy and as an instrument for personal devotion and social self-representation. However, the inscriptions that cohabit with the cult images offer a different interpretative spectrum. Therefore, their analysis cannot be limited to the same schemes used for the study of the image and its social function. It is essential to first understand who the potential audience is that will be looking at these inscriptions to discern their functions within society. As mentioned above, many of them are imperceptible to the eye and therefore cannot convey a message to anyone at a certain distance from them. In this sense, only those who had access to the chapels —the owners or the clergy attending to religious obligations— could be close enough to identify and read some of the inscriptions. Therefore, it is the patrons of the works themselves and their closest circles who make up the core group of receptors of the pictorial inscriptions. Thus, the public is made up of ecclesiastics, nobles, patricians and liberal professionals, all of whom had a close relationship with written culture and who, at a given moment, were the ones who selected the epigraphic programme that they and their successors would consume.

28Knowing the people who made up the audience, it is necessary to consider what the functions of these texts were. Given their location, physical characteristics, and content, we should rule out the pedagogical vocation of the epigraphs studied and their function as a support for sermons. On the contrary, they would have had a devotional and liturgical purpose. As the faithful were not an active part of the Eucharistic celebrations, the images could be used to concentrate on their personal devotions. In front of an altarpiece, they could discover the inscriptions on the paintings and read them. In the case of the illiterate, the iconicity of writing would come into play, giving the impression that the textual content, simply because it was written, was of the utmost importance.

29However, this liturgical function would not explain the arrangement of many texts with significant limitations for viewing and reading. This makes it clear that reading and, consequently, the transmission of a particular message is neither the main nor the only objectives of the inscriptions on the painting. It could therefore be affirmed that the purpose of all inscriptions, regardless of the circumstances of their visibility, is to make certain words present over time in a specific space thanks to their epigraphic nature, which guarantees the permanence of the writing.

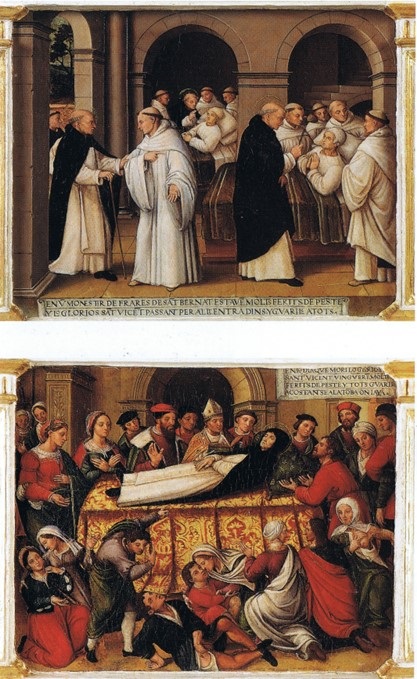

30More interesting are the inscriptions which not only have the characteristics of visibility and legibility, but whose format shows that they were conceived to be appreciated and read47. Some of them have an explanatory function, identifying characters and detailing the scenes in which they are located. Due to their nature, these epigraphs should be easily read by the public, which means that they form one of the groups with the greatest presence of Valencian language. A clear example is the cartouches of the two scenes on the bench of the altarpiece of Saint Vincent Ferrer, which explain two miracles of the friar preacher (fig. 10). Another group of inscriptions is made up of those that can only be understood in relation to the images and vice versa, this is, the images can only be understood when the text is read. Thus, there are enigmatic paintings with a set of epigraphs that can only be understood by reading them. This is the case of the Virgin of Hope by Joanes which, given that it does not depict her pregnancy, is only known when the text of the episode of the Incarnation is read (fig. 11). A new set of inscriptions provides complementary readings of the theme they accompany. In this sense, the image is understandable by itself, but the epigraphic programme provides the reader capable of unravelling it with a new interpretative dimension, like the texts of the Dance of Death in Morella. Lastly, there are those texts which neither really explain the image nor complement it, but which are not useful for interpreting its content. They are, rather, a detail of the designer of the painting. A clear example are those books that contain a text not for its content, but for the realistic representation of this object, such as the portrait of Alfonso the Magnanimous and the book with a fragment of De bello ciuili (fig. 12).

Fig. 10. Didascalia in Valencian. «En un monestir de frares de Sant Bernat estaven molt ferits de peste y lo gloriós sant Vicent, passant per allí, entrà y guarí’ls a tots»; «En lo dia que morí lo gloriós sant Vicent, vingueren molt ferits de peste y tots guariren acostant-se a la tomba on jaÿa». Segorbe, Museo Catedralicio. Altarpiece of Saint Vincent Ferrer, Vicent Macip and Joanes (post 1523. Detail. Benito Doménech-Galdón, 1997: 84-87.

Fig. 11. Valencia, Museu de Belles Arts. Virgin of Hope, Joanes, ca. 1555. Gimilio Sanz, 2020: 40-41.

Fig. 12. Zaragoza, Museo de Zaragoza. King Alfonso the Magnanimous, Joanes, 1557. Detail.

V. In conclusion

31It would be difficult to extract conclusions from a text which is based on the conclusions of my thesis, thereby seeking absolute synthesis. For this reason, I feel it would be a bit reiterative to summarise the summary and list again the characteristics and functions of these texts. However, I would like to conclude with a brief reflection, more focused on the future than on the present. The inscriptions on the paintings, despite their apparent simplicity, offer many elements that invite reflection on the functioning of the mentality and religiosity of the late Middle Ages and early Modern period, as well as on the functioning of the scripts displayed in past societies. This allows new ways of study to be explored, in which this article is merely the beginning, the establishment of a methodology and a working strategy that will hopefully bear fruit soon.

VI. Bibliography

32Baxandall, Michael, Painting and experience in Fifteenth century Italy. A primer in the social history of pictorial style, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1972.

33Benito Doménech, Fernando, Galdón, José Luis, Vicent Macip (h. 1475-1550), Valencia, Generalitat Valenciana, 1997.

34Benito Doménech, Fernando, Gómez Frechina, José (eds.), La memoria recobrada. Pintura valenciana recuperada de los siglos xiv y xv, Valencia, Generalitat Valenciana, 2005.

35Bravi, Giulio Orazio, Recanati, Maria Grazia (eds.), Taccuino di disegni di Giovannino de Grassi: Biblioteca CIvica “Angelo Mai” di Bergamo Cassaf. 1.21, Modena, Il Bulino, 2003.

36Company Climent, Ximo (coord.), Restauració del retaule major de l’Església de Sant Feliu de Xàtiva, Valencia, Generalitat Valenciana, 2005.

37Company Climent, Ximo, Paolo da San Leocadio i els inicis de la pintura del Renaixement a Espanya, Gandía, CEIC Alfons el Vell, 2006.

38Company Climent, Ximo et al. (eds.), Documents de la pintura valenciana medieval i moderna, I (1238-1400), Valencia, Publicacions de la Universitat de València, 2005.

39Debiais, Vincent, «Construcción epigráfica y uso funerario del retablo de la Pasión de los Caparroso: herencia isidoriana e influencia litúrgica», Príncipe de Viana 242 (2007), 797-813.

40Debiais, Vincent, Messages de pierre. La lecture des inscriptions dans la communication médiévale (xiiie-xive siècle), Turnhout, Brepols, 2009.

41Debiais, Vincent, «Le chant des formes. L’écriture épigraphique entre matérialité du tracé et transcendance des contenus», Revista de poética medieval 27 (2013), 101-129.

42Debiais, Vincent, «Mostrar, significar, desvelar. El acto de representar según las inscripciones medievales», Codex aquilarensis: Cuadernos de investigación del Monasterio de Santa María la Real 29 (2013), 169-186.

43Debiais, Vincent, «Intención documental, decisiones epigráficas. La inscripción medieval entre el autor y su audiencia», Marchant Rivera, Alicia and Barco Cebrián, Lorena (eds.), Escritura y sociedad: el clero, Albolote, Editorial Comares, 2019, 65-78.

44Debiais, Vincent, «Visibilité et présence des inscriptions dans l’image médiévale», Brodbeck, Sulamith and Poilpré, Anne-Orange (eds.), Visibilité et présence de l’image dans l’espace ecclésial. Byzance et Moyen Âge occidental, París, Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2019, 357-378.

45Favreau, Robert, Les inscriptions médiévales, Turnhout, Brepols, 1979.

46Favreau, Robert, Épigraphie médiévale, Turnhout, Brepols, 1997.

47Flett, Alison R., «The significance of texts scrolls: towards a descriptive terminology»,

48Manion, Margaret M. and Muir, Bernard J. (eds.), Medieval texts and images. Studies of manuscripts from the Middle Ages, Chur (etc.), Harwood Academic Publisshers, 1991, 43-56.

49Framis Montoliu, Maite, «Los Cabanes: más de un siglo de vínculos familiares y laborales entre los pintores de la ciudad de Valencia (1422-1576)», Hernández Guardiola, Lorenzo (coord.), De pintura valenciana (1400-1600). Estudios y documentación, Alicante, Instituto Alicantino de Cultura «Juan Gil-Albert», 2006, 149-210.

50Gell, Alfred, Art and agency. An anthropological theory, Oxford-New York, Clarendon Press, 1998.

51Gimeno Blay, Francisco M. «”[...] E féu vot de ell scriure lo seu nom en les portes de la ciutat”: mensajes en catalán en las filacterias de la pintura bajomedieval», Ciociola, Claudio (dir.), «Visibile parlare». Le scritture esposte nei volgari italiani dal Medioevo al Rinascimento, Naples, Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, 1997, 101-133.

52Gimeno Blay, Francisco M. and Trenchs Òdena, José, «La escritura medieval de la Corona de Aragón (1137-1474)», Anuario de Estudios Medievales, 21 (1991), 493-511.

53Gimeno Blay, Francisco M., Admiradas mayúsculas. La recuperación de los modelos gráficos romanos, Salamanca, Instituto de Historia del Libro y de la Lectura, 2005.

54Gimeno Blay, Francisco M., Scripta manent. De las ciencias auxiliares a la historia de la cultura escrita, ed. by María Luz Mandingorra Llavata and José Vicente Boscá Codina, Granada, Universidad de Granada, 2008.

55Gimilio Sanz, David (dir.), Més Museu. Últimes adquisicions del Museu de Belles Arts de València (2010-2020), Valencia, Conselleria d’Educació, Ciència i Esport, 2020.

56Jolivet-Lévy, Catherine, «Inscriptions et images dans les églises byzantines de Cappadoce. Visibilité/lisibilité, interactions et fonctions», Brodbeck, Sulamith and Poilpré, Anne-Orange (eds.), Visibilité et présence de l’image dans l’espace ecclésial. Byzance et Moyen Âge occidental, París, Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2019, 379-408.

57Macián Ferrandis, Julio, «Oÿu, maleÿts, al Redemtor. Los textos apocalípticos en vulgar en la pintura valenciana (ss. xiv-xv)», Marsilla de Pascual, Francisco R. and Beltrán

58Corbalán, Domingo (eds.), De scriptura et scriptis: consumir. Actas de las XVII Jornadas de la Sociedad Española de Ciencias y Técnicas Historiográficas, Murcia, Fundación Cajamurcia-Universidad de Murcia (Servicio de Publicaciones), 2021, 561-582.

59Macián Ferrandis, Julio, «Un llibre a les mans de la Verge. Pintura i escriptura en la taula de la Mare de Déu de l’Esperança de Joan de Joanes», Saitabi 71 (2021), 59-75.

60Macián Ferrandis, Julio, Studiose litteras in picturis attendere. Estudi i edició de les inscripcions de la pintura valenciana (1238-1579), unpublished Doctoral Thesis, Valencia, Universitat de València, 2022.

61Macián Ferrandis, Julio, «Quis est dignus aperire librum ? La representació pictòrica del llibre medieval: formats i escriptura», Gimeno Blay, Francisco M. and Iglesias-Fonseca, J. Antoni (eds.), Ut amicitiam omnibus rebus humanis anteponatis. Miscelánea de estudios en homenaje a Gemma Avenoza Vera, Valencia, Publicacions de la Universitat de València, 2023, 303-313.

62Macián Ferrandis, Julio, «Axí en les letres gòtigues com en altres parts de la dita pintura. Casos de multigrafismo en la pintura valenciana cuatrocentista», Rodríguez Suárez, Natalia (ed.), La escritura en los siglos xv y xvi. Una eclosión de pluralidad gráfica, in press.

63Macián Ferrandis, Julio, «Qui legit, intelligat. La palabra escrita en la pintura medieval y moderna valenciana», García Mahíques, Rafael, Mocholí Martínez, María Elvira (eds.), La interdisciplinariedad en el estudio de la imagen. Anejos de Imago 9, Valencia, Servei de Publicacions de la Universitat de València, in press.

64Macián Ferrandis, Julio and Garcia Femenia, Alfredo, «Las prácticas de escritura de los pintores valencianos: los casos de Paolo de San Leocadio, Nicolau Falcó y Joan de Joanes», Erasmo. Revista de Historia Bajomedieval y Moderna 8 (2021), 43-69: https://doi.org/10.24197/erhbm.8.2021

65Molina de la Torre, Francisco J., «Escritura e imagen. Una aproximación paleográfica a la obra de Nicolás Francés», Herrero de la Fuente, Marta (et al.), Alma Littera. Estudios dedicados al profesor José Manuel Ruiz Asencio, Valladolid, Universidad de Valladolid, 2014, 451-466.

66Montero Tortajada, Encarnación, «El cuaderno de dibujos de los Uffizi: un ejemplo, tal vez, de la transmisión del conocimiento artístico en Valencia en torno a 1400», Ars longa. Cuadernos de arte 22 (2013), 55-75.

67Montero Tortajada, Encarnación, La transmisión del conocimiento en los oficios artísticos. Valencia, 1370-1450, Valencia, Institució Alfons el Magnànim, 2015.

68Moreno Coll, Araceli, «Pervivencia de motivos islámicos en el Renacimiento: el lema “ʼIzz Li-Mawlana Al-Sultan” en las puertas del retablo mayor de la catedral de Valencia», Espacio, tiempo y forma. Serie VII: Historia del Arte 6 (2018), 237-258.

69Petrucci, Armando, La scrittura. Ideologia e rappresentazione, Turin, Giulio Einaudi, 1986.

70Pozzi, Giovanni, «Dall’ordo del ‘Visibile Parlare’», Ciociola, Claudio (dir.), ‘Visibile parlare’. Le scritture esposte nei volgari italiani dal Medioevo al Rinascimento, Naples, Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, 1997, 11-41.

71Rodríguez Suárez, Natalia, «Paleografía epigráfica: la transición hacia la letra gótica minúscula en las inscripciones españolas», Martín López, María Encarnación and García Lobo, Vicente (eds.), Las inscripciones góticas. II Coloquio Internacional de Epigrafía Medieval, León, Corpus Inscriptionum Hispaniæ Mediævalium, 2010, 469-477.

72Rodríguez Suárez, Natalia, «La escritura prehumanística en España: novedades sobre su cronología», Martín López, María Encarnación (ed.), De scriptura et scriptis: producir, León, Universidad de León. Área de Publicaciones, 2020, 61-76.

73Sanchis Sivera, José, Pintores medievales en Valencia, Barcelona, Tipografia L’Avenç, Massí, Casas & Cª, 1914, facsimilar edition, Valencia, Librerías París-Valencia, 1996.

74Sanchis Sivera, José, «La escultura valenciana en la Edad Media. Notas para su historia», Archivo de Arte Valenciano 10 (1924), 3-29.

75Sanchis Sivera, José, «Pintores medievales en Valencia (conclusión)», Archivo de Arte Valenciano 16-17 (1930-1931), 3-116.

76Scheller, Robert W., Exemplum. Model-book Drawings and the Practice of Artistic Transmission in the Middle Ages (ca. 900-ca. 1450), Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, 1995.

77Sebastián López, Santiago, «La inscripción como clave y aclaración iconográfica», Fragmentos. Revista de arte, 17-18-19 (1991), 135-136.

78Tolosa Robledo, Lluïsa, Company Climent, Ximo and Aliaga Morell, Joan (eds.), Documents de la pintura valenciana medieval i moderna, III (1401-1425), Valencia, Publicacions de la Universitat de València, 2011.

79Wallis, Mieczysław, «Inscriptions in paintings», Semiotica (English Supplement), 9 (1973), 4-33.

80Yarza Luaces, Joaquín, «Artista-artesano en la Edad Media hispana», Yarza Luaces, Joaquín and Fité Llevot, Francesc (coords.), L’artista-artesà medieval a la Corona d’Aragó, Lerida, Edicions de la Universitat de Lleida, 1999, 7-58.

Notes

1 Since this is a summary of my doctoral thesis, many of the sections that constitute it are extremely abbreviated here, so it would be counterproductive to flood the text with footnotes. Therefore, only those approaches that have a specific or fundamental publication will be referenced, while for the rest, I refer to my PhD dissertation, which will soon be available in the virtual repository of the University of Valencia (Roderic): Macián Ferrandis, Julio, Studiose litteras in picturis attendere. Estudi i edició de les inscripcions de la pintura valenciana (1238-1579), unpublished Doctoral Thesis, Valencia, Universitat de València, 2022.For a more detailed historiographical treatment, I refer to pages 10-13 and 146-169.

2 Petrucci, Armando, La scrittura. Ideologia e rappresentazione, Turin, Giulio Einaudi, 1986.

3 Defined as «the interdisciplinary space [...] that studies the processes of production of written testimonies, the different forms of use, as well as the devices that have guaranteed their preservation over time». Gimeno Blay, Francisco M., Scripta manent. De las ciencias auxiliares a la historia de la cultura escrita, ed. by María Luz Mandingorra Llavata and José Vicente Boscá Codina, Granada, Universidad de Granada, 2008, 129.

4 For example, Favreau, Robert, Les inscriptions médiévales, Turnhout, Brepols, 1979 o idem, Épigraphie médiévale, Turnhout, Brepols, 1997.

5 Gimeno Blay, Francisco M. «”[...] E féu vot de ell scriure lo seu nom en les portes de la ciutat”: mensajes en catalán en las filacterias de la pintura bajomedieval», Ciociola, Claudio (dir.), «Visibile parlare». Le scritture esposte nei volgari italiani dal Medioevo al Rinascimento, Naples, Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, 1997, 101-133.

6 The works of Professor Natalia Rodríguez Suárez stand out, such as «La escritura prehumanística en España: novedades sobre su cronología», Martín López, María Encarnación (ed.), De scriptura et scriptis: producir, León, Universidad de León. Área de Publicaciones, 2020, 61-76.

7 I would like to take this opportunity to thank Professor Debiais for his interest in my work and for the great help he has always given me.

8 Other authors have made similar systematisations based on works of European art, so their conclusions are more general: Wallis, Mieczysław, «Inscriptions in paintings», Semiotica (English Supplement), 9 (1973), 6-7; Sebastián López, Santiago, «La inscripción como clave y aclaración iconográfica», Fragmentos. Revista de arte, 17-18-19 (1991), 136; or Molina de la Torre, Francisco J., «Escritura e imagen. Una aproximación paleográfica a la obra de Nicolás Francés», Herrero de la Fuente, Marta (et al.), Alma Littera. Estudios dedicados al profesor José Manuel Ruiz Asencio, Valladolid, Universidad de Valladolid, 2014, 457-458.

9 Wallis, Mieczysław, «Inscriptions in paintings»..., 6.

10 Flett, Alison R., «The significance of texts scrolls: towards a descriptive terminology«, Manion, Margaret M. and Muir, Bernard J. (eds.), Medieval texts and images. Studies of manuscripts from the Middle Ages, Chur (etc.), Harwood Academic Publishers, 1991, 43-56.

11 Macián Ferrandis, Julio, «Quis est dignus aperire librum? La representació pictòrica del llibre medieval: formats i escriptura», Gimeno Blay, Francisco M. and Iglesias-Fonseca, J. Antoni (eds.), Ut amicitiam omnibus rebus humanis anteponatis. Miscelánea de estudios en homenaje a Gemma Avenoza Vera, Valencia, Publicacions de la Universitat de València, 2023, 303-313.

12 Gimeno Blay, Francisco M. and Trenchs Òdena, José, «La escritura medieval de la Corona de Aragón (1137-1474)», Anuario de Estudios Medievales, 21 (1991), 505-508; Rodríguez Suárez, Natalia, «Paleografía epigráfica: la transición hacia la letra gótica minúscula en las inscripciones españolas», Martín López, María Encarnación and García Lobo, Vicente (eds.), Las inscripciones góticas. II Coloquio Internacional de Epigrafía Medieval, León, Corpus Inscriptionum Hispaniæ Mediævalium, 2010, 471-472.

13 Gimeno Blay, Francisco M. and Trenchs Òdena, José, «La escritura medieval de la Corona de Aragón (1137-1474)»..., 505-507.

14 Macián Ferrandis, Julio, «Axí en les letres gòtigues com en altres parts de la dita pintura. Casos de multigrafismo en la pintura valenciana cuatrocentista», Rodríguez Suárez, Natalia (ed.), La escritura en los siglos xv y xvi. Una eclosión de pluralidad gráfica, in press.

15 Macián Ferrandis, Julio, «Un llibre a les mans de la Verge. Pintura i escriptura en la taula de la Mare de Déu de l’Esperança de Joan de Joanes», Saitabi 71 (2021), 59-75.

16 Macián Ferrandis, Julio, «Oÿu, maleÿts, al Redemtor. Los textos apocalípticos en vulgar en la pintura valenciana (ss. xiv-xv)», Marsilla de Pascual, Francisco R. and Beltrán Corbalán, Domingo (eds.), De scriptura et scriptis: consumir. Actas de las XVII Jornadas de la Sociedad Española de Ciencias y Técnicas Historiográficas, Murcia, Fundación Cajamurcia-Universidad de Murcia (Servicio de Publicaciones), 2021, 561-582.

17 Moreno Coll, Araceli, «Pervivencia de motivos islámicos en el Renacimiento: el lema “ʼIzz Li-Mawlana Al-Sultan” en las puertas del retablo mayor de la catedral de Valencia», Espacio, tiempo y forma. Serie VII: Historia del Arte 6 (2018), 237-258.

18 Debiais, Vincent, Messages de pierre. La lecture des inscriptions dans la communication médiévale (xiiie-xive siècle), Turnhout, Brepols, 2009, 63; idem, «Le chant des formes. L’écriture épigraphique entre matérialité du tracé et transcendance des contenus», Revista de poética medieval 27 (2013), 101-129; idem, «Mostrar, significar, desvelar. El acto de representar según las inscripciones medievales», Codex aquilarensis: Cuadernos de investigación del Monasterio de Santa María la Real 29 (2013), 169-186; idem, «Visibilité et présence des inscriptions dans l’image médiévale», Brodbeck, Sulamith and Poilpré, Anne-Orange (eds.), Visibilité et présence de l’image dans l’espace ecclésial. Byzance et Moyen Âge occidental, París, Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2019, 357-378.

19 Gell, Alfred, Art and agency. An anthropological theory, Oxford-New York, Clarendon Press, 1998, 18-19; Debiais, Vincent, «Construcción epigráfica y uso funerario del retablo de la Pasión de los Caparroso: herencia isidoriana e influencia litúrgica», Príncipe de Viana 242 (2007), 811; idem, «Mostrar, significar, desvelar. El acto de representar según las inscripciones medievales»...

20 Debiais, Vincent, «Intención documental, decisiones epigráficas. La inscripción medieval entre el autor y su audiencia», Marchant Rivera, Alicia and Barco Cebrián, Lorena (eds.), Escritura y sociedad: el clero, Albolote, Editorial Comares, 2019, 65-78.

21 Jolivet-Lévy, Catherine, «Inscriptions et images dans les églises byzantines de Cappadoce. Visibilité/lisibilité, interactions et fonctions», Brodbeck, Sulamith and Poilpré, Anne-Orange (eds.), Visibilité et présence de l’image dans l’espace ecclésial. Byzance et Moyen Âge occidental..., 379-408.

22 Debiais, Vincent, Messages de pierre. La lecture des inscriptions dans la communication médiévale (xiiie-xive siècle)..., 15.

23 Pozzi, Giovanni, «Dall’ordo del ‘Visibile Parlare’», Ciociola, Claudio (dir.), ‘Visibile parlare’. Le scritture esposte nei volgari italiani dal Medioevo al Rinascimento, Naples, Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, 1997, 32.

24 Macián Ferrandis, Julio, Studiose litteras in picturis attendere. Estudi i edició de les inscripcions de la pintura valenciana (1238-1579)..., 171-176.

25 Macián Ferrandis, Julio, Studiose litteras in picturis attendere. Estudi i edició de les inscripcions de la pintura valenciana (1238-1579)..., 176-183.

26 Arxiu del Regne de València (ARV), Protocol de Francesc Saidia, n. 3.002. 1394, April, 21. Valencia. Company Climent, Ximo et al. (eds.), Documents de la pintura valenciana medieval i moderna, I (1238-1400), Valencia, Publicacions de la Universitat de València, 2005, 384-385.

27 Montero Tortajada, Encarnación, La transmisión del conocimiento en los oficios artísticos. Valencia, 1370-1450, Valencia, Institució Alfons el Magnànim, 2015, 606-608.

28 Sanchis Sivera, José, «La escultura valenciana en la Edad Media. Notas para su historia», Archivo de Arte Valenciano 10 (1924), 17-19.

29 Yarza Luaces, Joaquín, «Artista-artesano en la Edad Media hispana», Yarza Luaces, Joaquín and Fité Llevot, Francesc (coords.), L’artista-artesà medieval a la Corona d’Aragó, Lerida, Edicions de la Universitat de Lleida, 1999, 15.

30 Baxandall, Michael, Painting and experience in Fifteenth century Italy. A primer in the social history of pictorial style, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1972, 45.

31 Scheller, Robert W., Exemplum. Model-book Drawings and the Practice of Artistic Transmission in the Middle Ages (ca. 900-ca. 1450), Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, 1995.

32 «Many papers with drawn pictures of the deceased's profession». Arxiu del Col·legi del Corpus Christi de València (ACCV), Notal de Bartomeu Martí, n. 68. 1418, April, 16. Valencia. Tolosa Robledo, Lluïsa, Company Climent, Ximo and Aliaga Morell, Joan (eds.), Documents de la pintura valenciana medieval i moderna, III (1401-1425), Valencia, Publicacions de la Universitat de València, 2011, 484.

33 Macián Ferrandis, Julio and Garcia Femenia, Alfredo, «Las prácticas de escritura de los pintores valencianos: los casos de Paolo de San Leocadio, Nicolau Falcó y Joan de Joanes», Erasmo. Revista de Historia Bajomedieval y Moderna 8 (2021),43-69: https://doi.org/10.24197/erhbm.8.2021

34 Macián Ferrandis, Julio, Studiose litteras in picturis attendere. Estudi i edició de les inscripcions de la pintura valenciana (1238-1579)..., 191-202.

35 «a crucifix like the one on the altarpiece of saint Augustine». Arxiu Eclesiàstic de Morella (AEM), Protocol de Guillem Esteve. 1388, January, 21. Morella. Company Climent, Ximo et al. (eds.), Documents de la pintura valenciana medieval i moderna, I (1238-1400)..., 300-301.

36 «The images of saints that the said illustrious Duchess will want and choose». Archivo Histórico de la Nobleza (AHNob), Osuna. Protocolo de Lluís Erau, leg. 1171-1. 1501, November, 29. Gandía. Company Climent, Ximo, Paolo da San Leocadio i els inicis de la pintura del Renaixement a Espanya, Gandía, CEIC Alfons el Vell, 2006, 470-472.

37 Arxiu Capitolar de València (ACV), vol. 3.661. 1441, April. 3. Valencia. Sanchis Sivera, José, Pintores medievales en Valencia, Barcelona, Tipografia L’Avenç, Massí, Casas & Cª, 1914, facsimilar edition, Valencia, Librerías París-Valencia, 1996, 70-71.

38 «The letters of the titulus of the Cross». Framis Montoliu, Maite, «Los Cabanes: más de un siglo de vínculos familiares y laborales entre los pintores de la ciudad de Valencia (1422-1576)», Hernández Guardiola, Lorenzo (coord.), De pintura valenciana (1400-1600). Estudios y documentación, Alicante, Instituto Alicantino de Cultura «Juan Gil-Albert», 2006, 190-192.

39 «At the feet of the Virgin Mary let there be an angel with a title that says “Assumpta est Maria in celum”». ACCV, Protocol de Cristòfol Fabra, n. 24.278. 1483, January, 15. Valencia. Sanchis Sivera, José, «Pintores medievales en Valencia (conclusión)», Archivo de Arte Valenciano 16-17 (1930-1931), 70-73.

40 Macián Ferrandis, Julio, Studiose litteras in picturis attendere. Estudi i edició de les inscripcions de la pintura valenciana (1238-1579)..., 202-210.

41 Montero Tortajada, Encarnación, «El cuaderno de dibujos de los Uffizi: un ejemplo, tal vez, de la transmisión del conocimiento artístico en Valencia en torno a 1400», Ars longa. Cuadernos de arte 22 (2013), 55-75.

42 Bravi, Giulio Orazio, Recanati, Maria Grazia (eds.), Taccuino di disegni di Giovannino de Grassi: Biblioteca CIvica “Angelo Mai” di Bergamo Cassaf. 1.21, Modena, Il Bulino, 2003, f. 29v.

43 «Notebooks written on paper in the form of a folio showing letter forms», «titled Formulari de letres». ACCV, Protocol d’Ambrosi Alegret, n. 1.107. 1452, November, 13. Valencia. Montero Tortajada, Encarnación, La transmisión del conocimiento en los oficios artísticos. Valencia, 1370-1450..., 446, 453.

44 Gimeno Blay, Francisco M., Admiradas mayúsculas. La recuperación de los modelos gráficos romanos, Salamanca, Instituto de Historia del Libro y de la Lectura, 2005.

45 Macián Ferrandis, Julio, Studiose litteras in picturis attendere. Estudi i edició de les inscripcions de la pintura valenciana (1238-1579)..., 211-228.

46 Macián Ferrandis, Julio, Studiose litteras in picturis attendere. Estudi i edició de les inscripcions de la pintura valenciana (1238-1579)..., 229-264.

47 Macián Ferrandis, Julio, «Qui legit, intelligat. La palabra escrita en la pintura medieval y moderna valenciana», García Mahíques, Rafael, Mocholí Martínez, María Elvira (eds.), La interdisciplinariedad en el estudio de la imagen. Anejos de Imago 9, Valencia, Servei de Publicacions de la Universitat de València, in press.

Pour citer ce document

Quelques mots à propos de : Julio Macián Ferrandis

Droits d'auteur

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/fr/) / Article distribué selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons CC BY-NC.3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/fr/)